| Diese Seite auf Deutsch! |

Snail Cultivation |

|

|

Part 2: Economic Use of Marine Snails | Part 3: Cowry Shells (Cypraeidae) | Part 4: Cone Shells (Conidae) |

Snail trader in Indelhausen (Lauter valleyl). |

In the German-speaking world, the Lauter Valley on the Swabian Jura became a centre of snail farming: the animals were collected, fattened, and shipped in barrels via Ulm and the Danube to Vienna, and later even to Paris. Commercial snail trading reached its peak in the 19th century, before the rise of modern preservation methods led to its decline.

According to the Fédération Française de l’Héliciculture, more than 300,000 tonnes of snails are consumed in France each year, a significant portion of which is imported, mainly from Eastern Europe, Turkey, North Africa, and Asia. Domestic snail farming accounts for only a small share of total consumption, with French production falling below 50,000 tonnes annually.

A large part of these imports comes from wild harvesting. From an ecological perspective, this is problematic: the origin is often difficult to trace, species identification is not always reliable, and the exploitation of wild populations threatens local populations. From a consumer perspective, this is also concerning.

French breeding efforts mainly focus on the escargot petit gris (the brown garden snail, Cornu aspersum), a hardy and undemanding species suitable for intensive rearing in open-air enclosures or greenhouses. To increase yields, certain farm strains with genetic origins in North Africa are used and marketed under the name Helix aspersa maxima, though this name is not scientifically correct. These breeds aim to resemble the prized Roman snail (Ecargot gros blanc, Helix pomatia) more closely in size and shell colour – though not in taste, which remains unmatched.

It is often claimed that Helix pomatia cannot successfully be bred on a commercial scale. However, this is only partially true, as the Roman snail has a long tradition of farming, particularly in southern Germany and especially on the Swabian Jura.

This page is dedicated to modern snail farming in its various forms – from naturalistic rearing to culinary uses.

Cultivated snail (Helix pomatia). Picture: Robert Nordsieck. |

Enclosures on a snail farm in Elgg (Switzerland). Picture: Robert Nordsieck. |

In the German-speaking world – especially in southern Germany and Austria – snail farming has seen a revival in recent decades. Many farms are now embracing open-air, naturalistic and sustainable methods that prioritise quality, traceability, and animal welfare. This "gentle snail farming" recalls the historical practices of Swabian snail farmers and avoids the use of pesticides or artificial fertilisers wherever possible. Instead, nitrogen-rich plants such as legumes and clover are cultivated, and green forage like chard or sunflowers is used for fattening snails.

Austria, too, is home to a growing number of snail farms: some with a focus on gastronomy, others on tourism. Some noble families even maintained their own snail gardens as early as the 18th century to meet demand for fasting dishes and culinary delicacies.

![]() Gugumuck.com: Viennese Snail Manufacture.

Gugumuck.com: Viennese Snail Manufacture.![]() Wikipedia:

Heliciculture.

Wikipedia:

Heliciculture.

|

Schneckenzucht: Weinbergschnecken halten und zubereiten. Unser Land (BR) on YouTube (In German). |

Particular attention is given to fencing: a metal barrier sunk deep into the ground prevents mice, shrews and other four-legged predators from entering. In addition, a fine-meshed plastic net keeps the snails from escaping. Bird netting, however, should be avoided – it would block the dew that is vital to the snails' survival. Instead, perches for birds of prey can be installed to attract natural predators of unwanted pests.

Soil composition is another key factor: a calcareous, alkaline soil supports shell growth and closely resembles the natural habitat of the Roman snail (Helix pomatia). Successful farming is generally possible wherever this species occurs naturally.

One particularly remarkable feature is the snails’ natural self-regulation: the mucus they leave behind while crawling contains chemical signal substances inhibiting the reproduction of other snails. Therefore, the maximum stocking density is around 20 snails per square metre – that is, roughly 3,300 animals in a 150–160 m² enclosure. To avoid overpopulation, it is thus advisable to manage several plots in parallel and move the animals to fresh plots after egg-laying.

Fertilisation also follows natural principles wherever possible: instead of artificial fertilisers, legumes such as clover are used to enrich the soil with nitrogen. Residual plants from the previous season are incorporated into the soil as green manure. Chemical pesticides are avoided altogether to prevent harmful residues in the edible flesh of the snails.

A balanced diet is essential for healthy, fast-growing snails – and for a high-quality final product. In naturalistic free-range farming, a diverse selection of plants is used to serve both as food and shelter.

Suitable green fodder includes robust, nutrient-rich plants that provide the snails not only with nourishment but also with shade and retreat areas. Particularly effective species include:

Chard - only one of the many possible food plants. Picture: Monika Samland, Dt. Institut für Schneckenzucht. |

Farm smail among clover plants. Picture: Robert Nordsieck. |

To prevent calcium deficiency, it is advisable to offer the snails calcium-rich minerals, for example crushed eggshells or specialised snail lime. This is typically made available in feeding trays or placed on stones so the animals can consume it as needed.

In general, the more varied the diet, the more robust, healthy, and flavourful the snails will be. And for those seeking to enhance the taste, targeted feeding with certain herbs, which was practised in historical snail farming, can even influence the aroma.

Roman snails (Helix pomatia) are hermaphrodites, meaning they possess both male and female reproductive organs. Nonetheless, reproduction usually involves mutual mating between two individuals, with each subsequently laying eggs. The mating process – often a spectacular display that includes the use of a so-called love dart – is followed by a waiting period of around 8 to 14 days before egg-laying.

Eggs are preferably deposited in loose, calcium-rich soil. The snails dig small holes into which they lay between 20 and 80 whitish, pea-sized eggs. These are carefully covered with soil. In a well-maintained breeding environment with soft substrate and sufficient moisture, egg-laying usually presents no difficulties – although it is important to check the soil regularly to avoid accidentally disturbing nesting sites. After 2 to 4 weeks, the young snails hatch. They are already fully formed but only a few millimetres in size and equipped with a thin, translucent shell. During the first few days, they require an especially high intake of calcium to harden their shells – so it is essential that they have access to calcium-rich food during this time.

In naturalistic free-range farming, juveniles are usually reared in separate enclosures, where they face less competition from adult snails. Once they have reached a certain size, they are transferred to fattening plots, where they continue feeding until they are ready for market. Rearing juveniles snails takes around 4 to 6 months – depending on weather conditions, location, and food availability. In cooler regions with a short growing season, development may take longer. For this reason, many breeders overwinter their snails outdoors and sell them the following year.

![]() Reproduction fo the Roman Snail (Helix

pomatia).

Reproduction fo the Roman Snail (Helix

pomatia).

|

Humane Treatment of Snails: When keeping and processing snails, it is essential to treat the animals with respect. Although snails possess a relatively simple nervous system, it is generally assumed that they are capable of at least basic pain perception. For culinary purposes, rapidly immersing the snails in boiling water is currently considered the most humane method: the animals die almost instantly, without prolonged suffering. In scientific work, humane methods of anaesthesia and euthanasia should likewise be observed. Placing live animals in alcohol is ethically problematic from an animal welfare perspective and also makes subsequent preparation more difficult. Whether in the kitchen, in farming, or in research – respectful treatment of animals should always be a matter of course. |

Snails with closed-up lids - ready for marketing. Picture: Monika Samland, Dt. Institut für Schneckenzucht. |

Before processing, the snails must be placed in boxes for several days, usually kept dry and without food. During this time, they empty their digestive tract. In traditional heliciculture, this step is known as "purging". Afterwards, the animals are briefly placed in cold water to stimulate activity before being killed by quickly blanching them in boiling water.

The next step involves removing the snails from their shells, discarding the visceral mass, and further processing the edible muscle tissue. In professional snail farming, the meat is either processed fresh, frozen, or sterilised and preserved in jars. Alternatively, it can be sold as a semi-preserved product or in gourmet packaging after being suitably dried.

Anyone wishing to collect and prepare wild snails from their garden should

not only be aware of the relevant legal regulations (in many countries, the

collection of wild Helix pomatia is prohibited or strictly regulated),

but also of the mandatory hygiene standards. Improper handling can pose health

risks, since for example, the snails might be infected with mites.

![]() Gugumuck.com: Werden Schnecken lebendig gekocht? (In German).

Gugumuck.com: Werden Schnecken lebendig gekocht? (In German).

![]() Gugumuck.com: Beim Ausnehmen hilft jeder mit! (In German).

Gugumuck.com: Beim Ausnehmen hilft jeder mit! (In German).

![]() Hartmut

Nordsieck auf hnords.de: Preparation (of snails before anatomical

inspection).

Hartmut

Nordsieck auf hnords.de: Preparation (of snails before anatomical

inspection).

Where snails are kept in larger numbers, their natural enemies are never far behind – especially in outdoor farming systems designed to replicate natural conditions. These predators can sometimes cause significant damage, particularly when they strike unnoticed during the night. The most important ones include:

On a snail farm, shrews have bitten open the shells of these Roman snails (Helix pomatia). Picture: Robert Nordsieck. |

![]() Map of the Snail

Farms in Germany and Austria.

Map of the Snail

Farms in Germany and Austria.

Even though industrial snail farming today is part of a global network, there are still regions where a particularly rich tradition of snail rearing has been preserved – for culinary, regional or simply passionate reasons.

In the German federal state of Baden-Württemberg, especially in the Swabian Jura mountains (Schwäbische Alb), the tradition of snail farming remains alive to this day. Here, it's not just about preserving historical roots, but also about exploring new approaches:

Austria, too, has developed a lively snail farming scene:

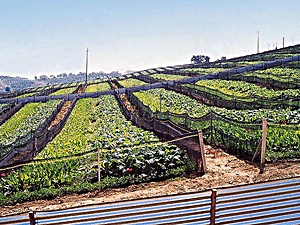

Heliciculture in Reinach, Auvergne, France. Picture: Association Aspersa (Source). |

Nonetheless, France has a long and institutionalised tradition of professional snail farming (héliciculture). As early as 1976, the Fédération française de l’héliciculture was founded – a national breeders’ association based in Dijon. Its aim was to define quality standards for breeding, feeding and marketing, and to establish snail farming as a recognised agricultural profession. Numerous other associations for snail breeders also exist across the country.

Primarily, two species are farmed in France: the escargot petit gris ("small grey snail"), Cornu aspersum (formerly known as Helix aspersa), is the most commonly bred species. It is hardy, highly fertile and fast-growing – ideal for mass production. There is also the escargot gros gris ("big grey snail"), Cornu aspersum maxima, a larger variety originated from North Africa, which is especially marketed because it vaguely looks like a Helix pomatia snail.

In 2021, there were between 350 and 400 snail farms in France, with an average area of 1,060 m². Of these, 84% raised only the standard Cornu aspersum (Petit Gris), 2% raised only Cornu aspersum maxima (Gros Gris), and 14% raised both variants.

![]() SIMONCELLI,

C. (2021): "Recensement national des entreprises hélicicoles". (National survey

of heliciculture businesses,

PDF).

SIMONCELLI,

C. (2021): "Recensement national des entreprises hélicicoles". (National survey

of heliciculture businesses,

PDF).

By contrast, the economic farming of the Roman snail (Helix pomatia), also known as the Escargot de Bourgogne ("Burgundy snail") or Gros Blanc ("big white snail"), is more challenging: It grows slowly, is more sensitive, and is protected in many regions. In France, the Roman snail is therefore almost exclusively available as a delicacy collected in the wild – and priced accordingly.

Farming methods in France range from intensive rearing in plastic-covered tunnels to outdoor systems inspired by the traditional snail farming practices of southern Germany. In both systems, targeted supplementary feeding is provided – typically using plant-based mixtures containing grains, bran, or legumes. Although the use of antibiotics and chemical additives is legally restricted, it is not entirely prohibited.

A notable cultural feature: in France, snail preparation is considered part of the breeding tradition. Snails are cleaned according to strict guidelines, briefly boiled, removed from their shells, and often refilled with garlic and herb butter – a method known worldwide as Escargots à la Bourguignonne. In the Mediterranean regions of France, the chocolate-band snail (Eobania vermiculata, locally known as Mourguette de Provence) is also bred, though primarily used in regional cuisine.

![]() Wikipedia:

Héliciculture (In French).

Wikipedia:

Héliciculture (In French).

Enclosures of a snail farm in Italy. Picture: Leonardo Dicorato (Source). |

Did You Know? Spanish Field Snail (Otala punctata). Source: Wikipedia. Called cabrilla in Spain, this species is collected from the wild, as is the closely related Milk Snail (Otala lactea).  The Chocolate Banded Snail (Eobania vermiculata), pictured here from Croatia, is often collected in Mediterranean France and Italy. In some areas, populations have become increa- singly rare. Picture: Andreas Gruber.  The Green Snail (Cantareus apertus) is mainly collected and partly farmed in southern Italy. This specimen is from Greece. Photo: Anna Chapman. |

Modern Italian snail farming largely follows the all’aperto method – that is, outdoor farming with natural vegetation and without additional heating or lighting systems. The goal is a particularly natural and high-quality product. The Roman snail (Helix pomatia) is rarely farmed in Italy. Instead, the brown garden snail (Cornu aspersum) dominates, mainly in the two varieties Cornu aspersum aspersum (Petit Gris) and Cornu aspersum maxima (Gros Gris), the same as in France.

A notable species is the chocolate band snail (Eobania vermiculata), sometimes also called the "vermicelli snail" in English due to its association with Mediterranean cuisine. This heat-loving snail is especially bred in southern Italy and on Sicily. Its flavour is described as particularly intense, making it a favourite in regional cooking. In southern Italy and Sicily, the green snail (Cantareus apertus) is also farmed.

The white dune snail (Theba pisana), by contrast, is not systematically cucltivated but mostly collected from the wild, particularly in the Mediterranean region – in parts of Spain, France, North Africa and Sardinia. Due to its rather social behaviour (it often climbs plant stems in groups to aestivate), it is easy to collect, which makes it attractive for wild harvesting but less suitable for controlled farming, as it is small and slow-growing.

Many Italian snail farms are members of the Associazione Nazionale Elicicoltori (ANE), which promotes quality standards and supports snail farming as a viable agricultural sector.

According to the Italian Wikipedia, Italy ranks as the fourth-largest producer of edible snails worldwide (after China, France and Spain), with an annual production of around 41,000 tonnes.

![]() Wikipedia:

Elicicoltura (In Italian).

Wikipedia:

Elicicoltura (In Italian).

Brown Garden Snail (Cornu aspersum) from Catalonia. Picture: Ferrean Turmo Gort (Source). |

Commercial snail farming has developed mainly in rural areas, with small to medium-sized farms. In addition to local sales and restaurant supply, some producers also export their snails – for example to France.

Farming methods:

|

In Portugal, caracóis are a popular summer snack, especially in Lisbon and the Alentejo. A typical preparation involves herbs such as oregano and bay leaf – ideally served with a cold beer.

Portuguese snail farming is generally less industrialised than in Spain, but there are a number of small, ambitious farms and sustainable farming projects, some of which receive EU funding as part of rural development initiatives.

![]() Wikipedia:

Helicicultura (In Spanish).

Wikipedia:

Helicicultura (In Spanish).

![]() Mediterranean Helicid Snail (Helicidae 3).

Mediterranean Helicid Snail (Helicidae 3).

![]() Field Snails (Otala).

Field Snails (Otala).

Enclosure in a snail farm in Petralona, Chalkidki, Greece. Picture: HelixPro Open Snail Farming. |

On the island of Crete in particular, snails are an integral part of the local diet. Dishes such as Kochlioí boubouristoí (fried snails with rosemary and vinegar) or Kochlioí yahni (snails in tomato sauce) are firmly rooted in the regional kitchen. While wild harvesting remains widespread – after rainfall, families often set out with buckets to collect them – organised snail farms are becoming increasingly common.

The most commonly farmed species here is Cornu aspersum, the same brown garden snail that is widely used as escargot petit gris in French and Italian heliciculture. Snails are usually raised in simple open-air enclosures, often combined with regionally adapted fodder plants.

On the Greek snail farm "Escargot de Crete", edible snails are farmed close to nature under olive trees. Picture: Escargot de Crete. |

Apart from the cultivated snails Cornu aspersum, there are several other edible snail species on Crete that are collected for consumption: The green snail (Cantareus apertus), Helix cincta, Helix nucula, the chocolate banded snail (Eobania vermiculata), and the white dune snail (Theba pisana).

Greece, standing between ancient tradition and modern agribusiness, is now on par with Europe's major "snail countries". Owed to the economic situation, there is also a great amount of snail collection in the wild. The consequences for local snail populations, however, need to be addressed.

![]() Escargot de Crete:

Snail farm of the Greek island of Crete.

Escargot de Crete:

Snail farm of the Greek island of Crete.

![]() Snail Farm and Fun: Snail Farm and Tourist Attraction on Crete.

Snail Farm and Fun: Snail Farm and Tourist Attraction on Crete.

![]() HelixPro Open Snail Farming, Petralona, Chalkidiki, Greece.

HelixPro Open Snail Farming, Petralona, Chalkidiki, Greece.

![]() Agrofarma

Hellas, Larissa, Griechenland - "The oldest snail farm in Greece".

Agrofarma

Hellas, Larissa, Griechenland - "The oldest snail farm in Greece".

The Csiga Farm, a snail farm in Mureș, Romania. Source: Csiga Farm (Csiga: Hungarian for Snail). |

A significant proportion of snails traded in Eastern Europe still comes from the wild. In rural parts of Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey, snail collecting is a long-standing springtime tradition. As soon as the weather warms, many people head to the woods and meadows to gather snails, which are then sold to intermediaries. These snails often end up in processing facilities and ultimately on European plates, with little to no traceability or species control. Helix lucorum, the banded Roman snail, is especially heavily harvested in Turkey and exported in large quantities.

However, this intensive collection has consequences: populations of Helix pomatia and Helix lucorum have already declined significantly in some areas. Within the European Union, there are increasing efforts to regulate wild harvesting and to encourage a shift toward controlled snail farming.

![]() GHEOCA, V. (2013): "Can Heliciculture act as a

tool for edible land snails' natural populations' management in Romania?".

Management of Sustainable Development. 5. 10. Sibiu, Romania (Link).

GHEOCA, V. (2013): "Can Heliciculture act as a

tool for edible land snails' natural populations' management in Romania?".

Management of Sustainable Development. 5. 10. Sibiu, Romania (Link).

Cybele Escargots, a snail farm in Türközü, Ayvalik, Balıkesir, Turkey. Source: Cybele Escargots. |

![]() Radio

Bulgaria:

How snails turned into a major Black Sea tourist attraction

(Snail farm

Eco-Telus in Balgarevo, Prov. Varna, Bulgaria).

Radio

Bulgaria:

How snails turned into a major Black Sea tourist attraction

(Snail farm

Eco-Telus in Balgarevo, Prov. Varna, Bulgaria).

Most snails produced in Eastern Europe are exported to France, Italy, and Spain, where they are served as delicacies in restaurants. France alone imports thousands of tonnes of snails from these countries every year. It is well known that some of the snails sold as "Escargot de Bourgogne" (Helix pomatia) are in fact imported from Eastern Europe – and in some cases, they are mislabelled and contain other species altogether. Often even the more colourful shells of Helix lucorum are marketed together with the meat of some other snail species, sometimes even of Giant African snails imported from West Africa (see below).

Giant African Land Snail (Archachatina marginata) on a mar- ket in Abidjan (Côte d'Ivoire). Picture: Thierry Thomas. |

In many West African countries, giant snails are considered a delicacy and are sold both on local markets and for export. Snails are typically farmed in open enclosures, with great emphasis placed on natural feeding methods to ensure high meat quality.

![]() Olokiki Husbandry: YouTube channel of a Nigerian snail farm with much

Information on various Achatina species and snail farming practices in Nigeria.

Olokiki Husbandry: YouTube channel of a Nigerian snail farm with much

Information on various Achatina species and snail farming practices in Nigeria.

Snail farming has also become established in Vietnam and China. Both Helix species and local snail varieties are bred in these countries. In Vietnam, snails are valued not only as a food source but also for their role in traditional medicine. In recent years, China has become an important exporter of snail products. Farming is often carried out on large-scale operations designed for maximum efficiency and output to meet demand from Europe and the United States. In some parts of Asia, colourful species of the genus Amphidromus are also bred, though more for decorative purposes than for consumption.

|

The Transatlantic Invasion! According to the University of California, several European snail species are now considered potential agricultural pests in the United States, including: - Brown Garden Snail (Cornu aspersum) - White Garden Snail (Theba pisana) - Netted Field Slug (Deroceras reticulatum) - Yellow Cellar Slug (Limacus flavus)  White Dune Snail (Theba pisana). Picture: O. Gargominy. Other sources also list the Leopard Slug (Limax maximus) among the introduced species. With the exception of Cornu aspersum, these snails were most likely not introduced because of commercial farming but rather via global trade and transport networks. Similar patterns of accidental introduction can also be observed within Europe. For instance, the Mediterranean Green Snail (Cantareus apertus) from Italy and Greece has been found outside its native range. |

Snail farming is less widespread in North America than in Europe, but there are several farms in Canada and the United States specialising in gourmet snail production. In recent years, there has been growing interest in regional and sustainable agriculture, which has also benefited snail farming. Some of these farms collaborate closely with high-end restaurants and focus on quality over quantity.

In the United States, Cornu aspersum is also spreading in the wild and is increasingly regarded as an agricultural pest. It is not always well documented whether the species was introduced through farming or by other means. The European Roman Snail (Helix pomatia) is also recorded as an introduced species in many parts of the USA, although it is rarely farmed. Numerous other European species have been introduced to North America and are sometimes viewed as pests. Tropical species such as the Giant African Snail (Lissachatina fulica – see above: USDA: Giant African Snails) were likely introduced for farming purposes but have become a serious threat to agricultural areas, particularly in places like the Hawaiian Islands. The subsequent introduction of tropical predatory snails (Euglandina rosea) to control them has, in turn, led to unforeseen consequences.

![]() Heliciculture.us,

Little Gray Farms: Starting a snail farm in Washington state (United

States).

Heliciculture.us,

Little Gray Farms: Starting a snail farm in Washington state (United

States).![]() US Department of Agriculture:

Snails and Slugs.

US Department of Agriculture:

Snails and Slugs.

There are also a few snail farms in Australia and New Zealand, mainly serving

the local market. These farms typically raise introduced species such as

Cornu aspersum. They are usually small in scale and focus on natural

farming practices.

Over the past few decades, snail farming has seen remarkable global development – evolving from traditional practices in European monasteries and rural farms to large-scale operations in France, Italy, Spain, and even parts of Africa and Asia. While Central and Southern Europe focus primarily on Helix pomatia and Cornu aspersum, countries in Africa and Southeast Asia increasingly rely on the Giant African Snail (Lissachatina fulica), prized for its rapid growth and resilience.

These varied approaches – from intensive indoor cultivation systems in France, to outdoor, nature-friendly farming in Germany and Austria, to wild harvesting in Eastern Europe – reflect the diverse strategies found in modern heliciculture. At the same time, global markets are undergoing change: with increasing awareness of sustainability and animal welfare, demand is shifting towards eco-conscious farming methods. More and more producers are turning to organic practices, natural feed sources, and deliberately avoiding chemical inputs – a trend particularly evident in the natural farming concepts of the Swabian Alb and Austria.

Meanwhile, snails are gaining culinary significance in regions not traditionally associated with their consumption. In Asia and Africa especially, the market is growing – supported by technological innovation and expanding international trade.

The future of snail farming is thus assured – and more dynamic than ever. Between traditional methods and modern technology, between mass production and sustainable agriculture, an industry is emerging that remains both economically and ecologically relevant.

And as they say in Siena: "Chiocciola – piano ma inesorabile.": The snail – slow, but unstoppable.

Latest Change: 03.07.2025 (Robert Nordsieck).