| Diese Seite auf Deutsch! |

|

Cowry Shells (Cypraeidae) |

| Part 1: Snail Cultivation (Terrestrial Snails) | Part 2: Economic Use of Sea Snails |

|

Part 4: Cone Shells (Conidae) |

|

|

Different cowry shells (Cypraeidae). Source: Wikipedia. |

Tiger cowry (Cypraea tigris), Queensland, Australia. Picture: Nathan Cook (iNaturalist). |

Cowries (family Cypraeidae) belong to the order Littorinimorpha and are found in tropical and subtropical seas across the globe.

Their most distinctive feature is the strikingly smooth, glossy shell, which is continually polished by the mantle lobes as they extend over the shell’s surface. Unlike many other sea snails, cowries’ shells remain flawless - they are not overgrown by algae or other marine organisms. The mantle also bears long, tentacle-like extensions called papillae (see photo above). The function of these structures is not entirely understood: they may help to camouflage the snail by disrupting its outline, or assist in absorbing oxygen through the skin. Another theory suggests that these papillae imitate the stinging appendages of nudibranchs (Nudibranchia), which may deter potential predators (see also: Egg cowries, Ovulidae).

![]() Waikiki Aquarium (Hawaii, USA):

Tiger Cowry.

Waikiki Aquarium (Hawaii, USA):

Tiger Cowry.

Cowry shells are typically oval to elongated in shape, relatively thick-walled, and have a porcelain-like sheen - which is why the German name for these snails translates as "porcelain snails". They come in a wide range of colours and patterns, from pure white to vibrant orange or speckled brown. Especially striking species include the tiger cowry (Cypraea tigris) and the serpent’s-head cowry (Monetaria caputserpentis). Due to their glossy surface, distinctive shape and vivid patterns, cowry shells have been collected by humans since prehistoric times - for economic, cultural or ritual purposes (see Cowries in Culture and Economy).

In total, around 200 species of Cypraeidae are known. Together with the closely related families of false cowries (Triviidae) and egg cowries (Ovulidae), they form the superfamily Cypraeoidea.

Cowry shells (Cypraeidae). Left: X-ray images (Picture: Michel Royon). Right: Top and bot- tom view of the tiger cowry Cypraea tigris. (Picture: Amir Ali Iranshahi). Source: Wikipedia. |

The shell of a buble snail (Bulla ampulla): Juvenile cowry shells have a similar form. Picture: Donna Pomeroy (iNaturalist): Kanton Is., Kiribati. |

![]() Table:

Mauritia arabica:

Shell Growth From Juvenile to Adult Cowry Shell.

Table:

Mauritia arabica:

Shell Growth From Juvenile to Adult Cowry Shell.![]() Denis W. Riek:

Juvenile stages of Cypraeidae shells.

Denis W. Riek:

Juvenile stages of Cypraeidae shells.

As the snail grows, the later whorls begin to envelop the earlier ones, eventually enclosing them completely inside the shell - a process known as involution. The result is the adult cowry’s characteristic smooth, domed shape (see image right), in which the original coiling is no longer visible from the outside and can only be seen in X-rays or by cutting the shell open.

The aperture (shell opening) on the underside is narrow and slit-like, and often reinforced with tooth-like ridges or lamellae. These features not only strengthen the shell but also protect the animal by making it harder for predators to reach the soft body inside.

Another notable trait is the durability of cowry shells. Once the aperture has fully formed - including its protective teeth - the shell no longer increases in size, but its walls continue to thicken. This makes cowries relatively well protected against smaller predators such as fish. Larger fish may swallow cowries whole, while species like pufferfish and stingrays are able to break the shells open. More specialised predators, such as octopuses or cone snails, use other strategies to overcome cowries (see Ecology).

This unique shell shape is found almost exclusively in cowries and their close relatives - it is one of the key features that sets the Cypraeoidea apart from other gastropods.

![]() Wikipedia:

Cowry Shells (Cypraeidae).

Wikipedia:

Cowry Shells (Cypraeidae).

![]() WoRMS: MolluscaBase eds. (2025):

Cypraeidae RAFINESQUE, 1815.

WoRMS: MolluscaBase eds. (2025):

Cypraeidae RAFINESQUE, 1815.

Cowries are dioecious: they have separate sexes, and fertilisation takes place internally. The female lays clusters of white, parchment-like egg capsules in which the larvae develop. In a remarkable behaviour for a snail, she protects the eggs by covering them with her foot until the veliger larvae hatch. These veliger larvae are planktonic and drift in the open water before undergoing their final transformation into juvenile snails and settling on the ocean floor to adopt a benthic lifestyle.

![]() Bailey-Matthews National Shell Museum and Aquarium:

Cowrie Larvae Hatch at Museum!

Bailey-Matthews National Shell Museum and Aquarium:

Cowrie Larvae Hatch at Museum!

Snakehead cowry shell (Monetaria caputserpentis) with extended mant- le lobes. Picture: Keith Willmott (iNaturalist): Western Australia. |

Atlantic deer cowry (Macrocypraea cervus), Florida Keys, USA. Picture: Kent Miller (iNaturalist). |

Cowries generally prefer shallow coastal waters with rocky substrates and seagrass meadows, and are especially common in the intertidal zone. Many species are also found on coral reefs, where they remain well hidden during the day. Some species, such as the tiger cowrie (Cypraea tigris), are also found in deeper waters, down to about 50 metres. During the day, cowries often hide under rocks or in coral crevices to avoid predators such as fish and octopuses, emerging at dusk to graze on algae and small sessile organisms growing on rocks and coral.

![]() PASSAMONTI,

M. (2015): The family Cypraeidae (Gastropoda Cypraeoidea) an unexpected case of

neglected animals. Biodiversity Journal 6 (1), pp. 449 - 466. (PDF).

PASSAMONTI,

M. (2015): The family Cypraeidae (Gastropoda Cypraeoidea) an unexpected case of

neglected animals. Biodiversity Journal 6 (1), pp. 449 - 466. (PDF).

While many species are nocturnal and well-camouflaged to avoid predation, there are also species with thick, heavy shells that actively crawl around in the open during the day to forage, such as the tiger cowry (Cypraea tigris), arguably the most well-known large cowry. Other species, like Mauritia mauritiana and the snake-head cowry (Monetaria caputserpentis, see above), have especially adapted shells with flat undersides, allowing them to cling tightly to the substrate with their strong foot, making it more difficult for predators to attack them.

Marbled cone snail (Conus marmoreus) approaching a mole cowry snail (Talparia talpa). Marshall Islands, Western Pacific. Picture: Scott und Jeanette Johnson (iNaturalist). |

Broken shell of a cowry (Mauritia arabica). It may have been attacked by a mangrove crab (Scylla serrata) or a stingray (Hemitrygon fluvio- rum). Picture: Denis K. Riek. |

Other predators have evolved specialized techniques to deal with adult cowries: The common octopus (Octopus vulgaris), for example, drills a hole into the shell and injects a paralyzing toxin. Cone snails (Conidae), such as the marbled cone snail (Conus marmoreus), ambush cowries and immobilize them with a venomous harpoon-like tooth.

![]() Denis W. Riek:

Cowry predation: Predatory gastropods?

Denis W. Riek:

Cowry predation: Predatory gastropods?

Juvenile cowries are especially vulnerable to predation, since their shells are not as thick yet as those of adults and thus offer less protection. Furthermore, their shell shape at this stage resembles that of bubble snails, with a greatly expanded aperture. Only in adulthood does the shell develop the typical narrow slit with protective denticles or ridges, which help guard the snail from predators (see Cowry Shell Morphology).

Some cowry species live in symbiosis with corals, which offer shelter within their branching structures, making it harder for predators to reach them. In return, the cowries help the corals by grazing away unwanted algal growth. In some regions, cowries are even considered indicators of reef health: A decline in their populations may point to excessive algal blooms or environmental degradation, while a stable population is often a sign of a healthy reef ecosystem with sufficient food and minimal disturbances.

|

False Cowry Snails (Triviidae)

From the Mediterranean to the Atlantic coast, the

coasts of Brittany, and along the western shores of Britain and Ireland, one can

find the shells of

Trivia monacha, which grow up to 12 mm in length. Due to the three

characteristic dark spots on its shell, it is commonly referred to as the

"spotted cowry" or coffee bean snail. Its shell surface is covered in distinct

ridges that contrast in colour with the rest of the shell. Unlike true cowries,

Trivia monacha does not possess an operculum (a shell lid). |

![]() Marine Gastropods on the Coast (on mullscs.at).

Marine Gastropods on the Coast (on mullscs.at).

A close relative that is often confused with Trivia monacha is the Arctic cowry, Trivia arctica. It is smaller in size and lacks the three coffee-like spots. Trivia arctica occurs in much the same geographical range as T. monacha, but is more common further north.

The European false cowries (family Triviidae) resemble the true cowries (Cypraeidae) in general shape and appearance, but are typically smaller and less conspicuous. They also differ in their diet: Trivia monacha (see box on the right) is a small carnivore that lives below the tide line and in the sublittoral zone, feeding on colonial tunicates (Tunicata). After mating in late spring or summer, the female places her bottle-shaped egg capsules inside the emptied tunicate colonies. From these capsules, free-swimming veliger larvae hatch and disperse through the plankton for several months.

Just like the true cowries, Trivia monacha has a distinctive shell in which the final whorl grows over all previous ones, hiding the typical spiral structure of the shell. However, the internal whorls remain clearly visible in X-ray images.

Juvenile Trivia snails up to about 5 mm in size still retain the typical coiled shell shape. Their aperture is wide and open, and not yet developed into the narrow, slit-like opening seen in adults.

![]() Wikipedia:

European

Cowry (Trivia monacha).

Wikipedia:

European

Cowry (Trivia monacha).

![]() WoRMS: MolluscaBase eds. (2025):

Triviidae TROSCHEL, 1863.

WoRMS: MolluscaBase eds. (2025):

Triviidae TROSCHEL, 1863.

![]() Fehse,

D., Grego, J., Manousis, T., Dieste, I.P. (2024): "Does

Trivia arctica occur in

the Mediterranean Sea?": Acta Conchyliorum 22.

Fehse,

D., Grego, J., Manousis, T., Dieste, I.P. (2024): "Does

Trivia arctica occur in

the Mediterranean Sea?": Acta Conchyliorum 22.

Egg cowry snail (Ovula ovum), New South Wales, Australia. Picture: Nick Lambert (iNaturalist). Picture right: Bottom side of an egg cowry shell (Ovula ovum). Picture: H. Zell. |

As in true cowries, the shell of many ovulids is at least convolute, meaning the final whorl grows over and covers the earlier ones. In Ovula ovum, the spire is completely hidden by the last whorl, while other species in the family - often referred to as spindle cowries - have elongated, spindle-shaped shells in which the spire remains visible from the outside.

Unlike true cowries, however, egg cowries are predatory snails. They live on corals or sea pens (Pennatulacea), feeding on the polyps of their hosts. Some species are even considered ectoparasitic, anchoring themselves to a coral with their muscular foot and consuming all polyps they can reach from that position.

As with Cypraeidae, the mantle lobes of Ovulidae can cover the shell almost entirely and help to keep it clean. Especially in juveniles, these mantle lobes often feature papillae similar to those of true cowries, providing camouflage and possibly mimicking nudibranchs (Nudibranchia), who famously have nettle cells in their dorsal appendages. This supports the theory that the papillae in true cowries may serve a similar function (see above).

Like cowries, ovulids undergo a planktonic veliger larval stage during their development. Systematically, the Ovulidae are considered a separate family within the superfamily Cypraeoidea, and are thus close relatives of both the Cypraeidae and the previously mentioned Triviidae (false cowries).

![]() Wikipedia:

Ovulidae.

Wikipedia:

Ovulidae.

![]() WoRMS: MolluscaBase eds. (2025):

Ovulidae J. FLEMING, 1822.

WoRMS: MolluscaBase eds. (2025):

Ovulidae J. FLEMING, 1822.

|

Cowry Shells - From Money to Writing! In China, cowrie shells were already in use more than 3,500 years ago. It is therefore no surprise that the Chinese character for a shell, 贝 (bèi), forms the root of many other characters related to wealth, value, or trade. 货 (huò) - Ware, Goods 财 (cái) - Wealth, Assets 贸 (mào) - Trade 贾 (jiǎ) - Trader, Merchant  Money cowry (Monetaria moneta). Source: Wikipedia. |

|

The Cowrie Trade: Trade Routes in Africa Cowrie shells were at the heart of extensive trade networks, especially in the Indian Ocean and West Africa. In the Indian Ocean, cowries from the Maldives and Sri Lanka were exported in large quantities to India and then further westward to Africa.  Arab traders with cowry shells. Source: Wikipedia. Particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries, this trade flourished and was, in part, controlled by European colonial powers such as the British. Cowries often arrived by ship on the coasts of West Africa, where they were exchanged for gold, ivory, and even enslaved people. These trade routes played a major role in the spread of cowrie shells as currency across the region. |

From China, cowry money spread further to India and Persia, where it appeared more than 2000 years ago. The word kauri itself originates from Hindi. In India, cowries reached peak usage between the 4th and 6th centuries AD and were still widely accepted in the 17th century, during Rembrandt's lifetime. They were even used in the Philippines. In fact, cowries remained in circulation in India until the mid-19th century, when British authorities abolished them as legal currency in 1872. Coin and cowry currencies coexisted in ancient India; finds from the 1st century AD include both forms. In Bengal and Siam, the related Monetaria annulus was used as currency from the 18th to the mid-19th century.

Most cowries used as currency came from the Maldives, an island group in the Indian Ocean. Even in the late 19th century, local men and women would collect them twice a month - with one person harvesting up to 12,000 shells per day.

Cowry shells were used as barter currency in Africa, Asia, and Oceania, often threaded into long strands. They symbolised wealth and power and played a major role in both local and long-distance trade. In West Africa, cowries were used as currency until colonial powers introduced coins and banknotes. Their shape and durability made them ideal for trade - and colonial powers took advantage of this: Especially British and Dutch merchants imported vast quantities of cowries from India to West Africa, using them to dominate local markets. At times, the influx of shells led to cowry inflation, as the supply grew too large.

Whole trade routes across West Africa revolved around cowries. Often imported from India or the Maldives, they were used to obtain gold, ivory, and tragically, also enslaved people. A single slave was sometimes priced at 25,000 cowry shells. This trade profited not only the colonial buyers, but also the predominantly Arab traders who sold enslaved individuals.

Cowries were also used as bride price - a symbolic compensation to the bride’s family.

![]() Wikipedia:

Shell Money.

Wikipedia:

Shell Money.![]() SCHILDER, M. (1952): Die Kaurischnecke. Geest &

Portig, Leipzig, S. 30 - 40.

SCHILDER, M. (1952): Die Kaurischnecke. Geest &

Portig, Leipzig, S. 30 - 40.

![]() HOGENDORN,

J., JOHNSON, M. (1986): The Shell Money of the

Slave Trade. Cambridge University Press.

HOGENDORN,

J., JOHNSON, M. (1986): The Shell Money of the

Slave Trade. Cambridge University Press.

Cowries have historically been highly valued as jewellery and ritual objects in many cultures across the world - even in inland regions far from the sea, suggesting long-established trade routes. Their shape and placement in graves of women and girls point to their symbolic meaning: often interpreted as a symbol for feminine fertility (due to their resemblance to female genitalia) or as a protective amulet against the "evil eye" (due to their eye-like appearance).

The earliest archaeological finds of cowries come from Neolithic China, around 6000 BCE. In the southern Levant, cowries were discovered mainly in the graves of young girls. The tradition seems to have spread to Egypt, where cowries were used as grave goods up until the Predynastic period (before 3100 BCE). Even later, they retained ritual significance - cowry motifs are found on amulets and seals from the second millennium BCE, although scarabs are more commonly known.

During the Hallstatt period (800-475 BCE), cowries were found in urn graves along the Vistula River. In Central Europe, cowries were primarily used in art and craft where they did not serve as currency. Their symbolic association with femininity and fertility is evidenced by finds across Europe well into post-Roman times - for instance, in the Mälaren region of Sweden around 900 AD.

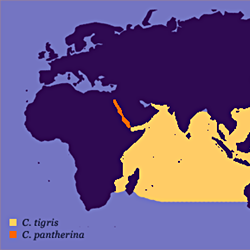

In south-western Germany and Switzerland during the Middle Ages women wore panther cowry shells (Cypraea pantherina) as fertility amulets and as protection against the "evil eye". Picture: Philipp66 (Wikipedia). |

Cowry shells on a traditional women's necklace by the Chuvash tatars, a Turkic people, that at one time inhabited an area from the Urals all the way to Siberia. Picture: Gennadij Ivanov/a> (Wikipedia). |

Even today, some women in Japan hold a cowry shell during childbirth.

![]() Wikipedia:

Cowry shells - Human Use (Englisch).

Wikipedia:

Cowry shells - Human Use (Englisch).

In more recent historical periods, cowries made their way into the decorative traditions of Central Asian peoples, such as the Chuvash Tatars, a Turkic group once spread from the Ural Mountains all the way to Siberia.

Among the Yoruba of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo, cowries were regarded as a medium of communication with the gods. They are used in rituals to divine answers for the faithful and appear in fortune telling and spiritual ceremonies. The cowry’s shiny, eye-like form symbolises fertility and protection, and burned cowry ash was believed to have medicinal properties.

Cowry shells) Picture: Salil Kumar Mukherjee (Wikipedia). |

|

Tamil dice game with cowry shells. Shells fallen with their aperture pointing up are counted, so this throw counts 3. Picture: Sodabottle (Wikipedia). |

Among the Ojibwa (Anishinaabe) of southern Canada, particularly near the Great Lakes, cowries ("miigis") play an important role in Midewiwin ceremonial practice. The Whiteshell Provincial Park in Manitoba, Canada is named after the white cowry shells that held deep spiritual meaning for local Indigenous groups.

In eastern India, especially Bengal, cowries were used in rituals to pay the ferryman of souls crossing the mythical Vaitarani River. They were associated with the goddess Lakshmi and symbolised prosperity. In Kerala, Kaniyar Panicker astrologers used cowries in divination.

Cowries also featured in gambling across India, Sri Lanka, and Nepal - similar to dice games: cowries were tossed, and only those that landed with their aperture showing up (which is rare) were counted.

|

A Very Rare Kind of Cowry Shell! Barycypraea fultoni is a rare species of cowry found in deep waters (60 to 250 metres) off the coasts of Mozambique and South Africa. Until 1970, only 25 specimens had ever been discovered. It was only with the growing rise of bottom trawling that living individuals began to be found more frequently.  Barycypraea fultoni, a very rare species of cowry snail. Mozambique. Picture: Lombry (iNaturalist) (Link). Due to its extreme rarity, this species is highly sought after by collectors and can fetch several thousand dollars per specimen. |

On the Fiji Islands, golden cowries (Cypraea aurantium) were worn as status symbols by local chieftains. In Tuvalu, cowries are still used in women’s traditional crafts.

Rare cowry shells are highly prized by collectors, often fetching thousands of dollars.

In Europe, large cowries such as the tiger cowry (Cypraea tigris) were once used as darning balls for mending socks. Even in the 1940s and 1950s, cowries were used in primary school maths lessons for counting, addition, and subtraction.

Cowries still feature prominently in the fashion world today. Whether worn as necklaces, bracelets, or headpieces, cowry shells are popular accessories in both traditional dress and modern "tribal" fashion.

Cowries are not only of historical importance - they also play a prominent role in modern times. In addition to their popularity in the fashion and jewellery industries, the brightly coloured, glossy shells of larger exotic species are highly sought after by shell collectors. Cowries have long been featured in natural history cabinets alongside other marine molluscs, and today they are still collected and traded, both locally - especially on tropical islands and in coastal regions - and internationally. Rare species from remote regions or individuals with unusual colour patterns can fetch exceptionally high prices.

One of the world’s largest shell dealers is Conchology Inc., run by Guido and Philippe Poppe, based in the Philippines. The company, which claims to offer more than 172,000 shells, operates under scientific guidance - both owners are recognised malacologists. However, many other shell dealers operate without such oversight.

![]() Conchology Inc.: Trading company for sea shells (and other shells) from all

over the world. There:

Cowrie Shells (Cypraeidae).

Conchology Inc.: Trading company for sea shells (and other shells) from all

over the world. There:

Cowrie Shells (Cypraeidae).

Due to increasing collecting pressure, combined with marine pollution and the degradation of coral reefs, the natural habitats of many cowry species are shrinking. Various organisations are now working on projects aimed at the sustainable use of cowries, in order to preserve the biodiversity of the affected regions. These include efforts such as controlled breeding programmes and the protection of particularly vulnerable populations.

Cowries are far more than just beautiful shells from the sea. Once used as currency, jewellery, and sacred objects across continents and millennia, they continue to captivate collectors, artists, and craftspeople around the world. As enchanting as these snails may be, protecting their natural habitats remains a vital task - to preserve not only the cultural legacy they represent but also the biological diversity of the world’s oceans.

Latest Change: 25.09.2025 (Robert Nordsieck).