| Diese Seite auf Deutsch! |

|

Aestivation |

Roman snails (Helix pomatia) aestivating at a former railway station in Breitenlee near Vienna. Photo: Robert Nordsieck. |

A membrane of dried mucus covers this Roman snail's apertu- re. Photo: Robert Nordsieck. |

Especially during dry weather, the snail's mucus coat might not be enough to protect it from the strong desiccation. So, it is then, that a snail withdraws into its shell and begins to cover the shell's open mouth (aperture) with mucus. In contact with the surrounding air, the mucus dries out and forms a thin membrane called a diaphragm.

Now the snail reduces almost all its life functions to the bare minimum and waits in this aestivating state until the air is sufficiently humid to support it, so it is not in danger of drying out.

In summer, Roman snails often spend the hot hours of the day entirely in aestivation, only coming out from their hiding places to forage for food in the evening. Roman snails often dig themselves into a hole to aestivate, also they might hide under roots and in the leaf litter on the ground. In shady and protected places several Roman snails can often be found.

Some snails also crawl up trees and plant stems, where the air is a little bit cooler than on the ground. Among those are door snails (Clausiliidae) and the so-called lapidary snail (Helicigona lapicida), a relative of Roman snails from the Helicidae snail family. Door snails are also very highly coiled so they can squeeze into crevasses in tree bark or rock surfaces to aestivate. For the same reason, the lapidary snail has a flat lenticular shell form.

There are also xerophilous snail species, such as the heath snails (Helicella, Xerolenta: Geomitridae), sandhill snails (Theba pisana) and zebra snails (Zebrina detrita: Enidae), which can endure times of drought. Their bright whitish shells protect them from desiccation by better reflecting the sunlight. Since the shell mouth (aperture) sticks to the surface the snail is hanging on, the snail is also protected from predators that might use the time when a snail is not active.

Terrestrial snails aestivating on the island of Lastovo in Croa- tia. Photos: Roland Schindler. |

|

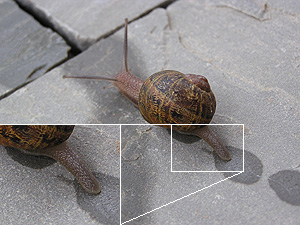

A "jumping" brown garden snail (Cornu aspersum), tail part enlarged. Photo: Robert Nordsieck. |

Especially in regions with lots of limestone, in especially hot summers it may happen that Roman snails do close their aperture with a calcareous lid to survive the time of drought. This is also a hint that Roman snails originally might have developed their hibernation lid from an aestivation lid in their original Mediterranean distribution zone.

Some snail species, such as the green snail (Cantareus apertus), which is at home in the Mediterranean, do build a calcareous shell lid exclusively for aestivation, since they never have to hibernate.

Some snails also adapt their way of locomotion to the weather: So brown garden snails (Cornu aspersum), for example, try to minimize the loss of moisture by a dry underground by moving in an awkward "jumping" fashion, only parts of the foot sole touching the ground and leaving a spotted slime thread behind.