| Diese Seite auf Deutsch! |

|

Economic Use of Sea Snails |

| Part 1: Snail Cultivation (Terrestrial Snails) |

|

Part 3: Cowry Shells (Cypraeidae) | Part 4: Cone Shells (Conidae) | ||

|

Section 1:

Section 2:

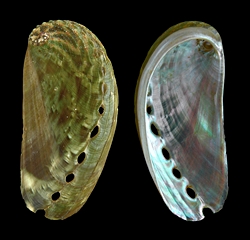

Marine snails have played an important role in human history for thousands of years. From antiquity to the present day, they have not only been used as food, but have also provided valuable raw materials such as dyes and mother-of-pearl. The spiky murex snails of the family Muricidae produced the famous Tyrian purple, a symbol of royal power and wealth, while the shells of abalones (Haliotidae) are prized for their iridescent inner surface and are still used in jewellery-making today – although much of this has now been replaced by synthetic materials.

But marine snails are also an integral part of the culinary traditions in many coastal regions across Europe, Asia and the Americas. Whelks (Buccinum undatum), periwinkles (Littorina littorea) and abalones (Haliotidae) regularly feature on local menus. The farming of these species has developed into a significant economic sector in many countries, supplying thousands of tonnes of snail meat annually.

In recent years, sustainability and the protection of marine ecosystems have come increasingly into focus. Overfishing and pollution are putting pressure on wild populations, and aquaculture is gaining importance as a result. While the cultivation of abalones and whelks is already established in several countries, sustainable methods of farming are now being explored for additional species as well.

The following sections provide an overview of economically important marine snails, highlighting their significance, uses, and the challenges they face today.

|

Did You Know? Rock snails, such as the banded dye-murex, are not always spiky: Bolinus brandaris lives on both soft sea floors and rocky substrates. On hard surfaces, however, the snails develop fewer and shorter spikes, which would otherwise prevent them from sinking into soft sediment. |

The ramose murex (Chicoreus ramosus) lives in the tropical Indo-Pacific and can grow to over 30 cm in length. Like other murex snails, it preys primarily on other molluscs, including snails and bivalves. Picture: H. Zell. |

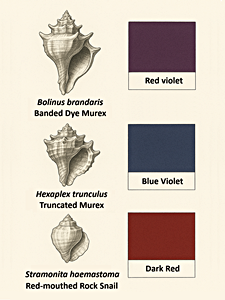

The most well-known representatives of the dye-producing muricids include:

|

Due to the threat posed by pollution – especially from tributyl tin (see section "Whelks") – Nucella lapillus is protected in the North and Baltic Seas under Germany’s Federal Species Protection Ordinance.

![]() GUCKELSBERGER,

M. (2013): Purple Murex Dye in Antiquity. Study paper at Iceland University,

Dep. of Philology, Latin, 2013. S. 8 - 12. (Link).

GUCKELSBERGER,

M. (2013): Purple Murex Dye in Antiquity. Study paper at Iceland University,

Dep. of Philology, Latin, 2013. S. 8 - 12. (Link).

![]() Purpurfärberei von der frühen Römischen Kaiserzeit bis zum Ende des

Byzantinischen Reiches (Wikipedia, in German).

Purpurfärberei von der frühen Römischen Kaiserzeit bis zum Ende des

Byzantinischen Reiches (Wikipedia, in German).

![]() Dog Whelk (Nucella lapillus) (Wikipedia).

Dog Whelk (Nucella lapillus) (Wikipedia).

![]() Nordische

Purpurschnecke, Steinchenschnecke (Nucella lapillus). In: WIESE,

V., JANKE, K.: Die Meeresschnecken und

-muscheln Deutschlands, S. 174. Quelle & Meyer Verlag 2021.

Nordische

Purpurschnecke, Steinchenschnecke (Nucella lapillus). In: WIESE,

V., JANKE, K.: Die Meeresschnecken und

-muscheln Deutschlands, S. 174. Quelle & Meyer Verlag 2021.

Murex snails are not only known for their use in purple dye production but also for their remarkable predatory lifestyle. As carnivorous gastropods, they feed primarily on other molluscs – including bivalves, other snails, and even members of their own species. Their hunting methods vary between species:

Red-mouthed rock snail (Stramonita haemastoma) near Lumio, Corsica. Picture: David Renoult (iNaturalist). |

Additionally, Stramonita injects a proteolytic enzyme to digest the soft tissues inside and a paralytic compound that prevents the mussel from effectively closing its shell. This hunting strategy poses a serious problem for oyster farms in the United States, where the species can cause significant economic losses.

![]() CARRIKER,

M. R. (1981): Shell penetration and feeding by naticacean and muricacean

predatory gastropods: a synthesis. Malacologia 20 (2), S. 403–422. (PDF;

7,3 MB).

CARRIKER,

M. R. (1981): Shell penetration and feeding by naticacean and muricacean

predatory gastropods: a synthesis. Malacologia 20 (2), S. 403–422. (PDF;

7,3 MB).

The banded dye-murex (Bolinus brandaris), by contrast, employs a different tactic: rather than drilling, it uses the reinforced edge of its shell as a lever to pry open the valves of bivalves. The tremendous leverage generated allows the snail to open its prey and consume the soft tissue within. Some other muricids are known to attack through the spines of their prey, bypassing the operculum, the horny door that normally seals the aperture.

This behaviour makes Bolinus brandaris a particularly efficient predator in Mediterranean waters. However, combined with increasing overfishing and pollution, this efficiency may also have ecological consequences for surrounding marine fauna.

![]() Bolinus brandaris: Article by Domenico

Pacifici on

Monaco Nature Encyclopedia.

Bolinus brandaris: Article by Domenico

Pacifici on

Monaco Nature Encyclopedia.

The truncated murex (Hexaplex trunculus) is a versatile predator that employs both techniques depending on the situation – it can bore or pry open shells, making it a flexible and highly successful hunter.

Purple snails and their dye colours. Schematic picture based on Wikipedia. |

Archaeological discoveries in Tyre and Sidon (in present-day Lebanon) reveal massive waste heaps of broken shells, clear evidence of the scale of ancient dye production. The process was not only complex, but also notoriously foul-smelling – for this reason, purple dye workshops were usually situated far outside of urban areas.

The purple dye is derived from a specialised glandular secretion produced by the hypobranchial gland of certain murex snails. This secretion contains complex precursor compounds, the most important of which are 6,6′-dibromoindigo (Tyrian purple) and 6-bromoindigo (a blue-violet pigment).

Initially, the secretion is colourless. Only upon exposure to light and oxygen does it develop the characteristic violet to purple hues. The chemical transformation is particularly fascinating: as the secretion dries, the brominated indigo precursors oxidise, resulting in the vibrant final pigment.

The precise shade produced depends on both the snail species and the processing conditions:

Once dried, the dye is remarkably lightfast and wash-resistant – properties that made it immensely sought after in antiquity. Due to its labour-intensive production and rarity, Tyrian purple at times was more valuable than gold and became a symbol of wealth and imperial power.

Today, Muricidae snails play virtually no role in the textile industry. The dye can be synthesised chemically, and the protection of these animals has taken precedence. Nevertheless, murex snails are frequently caught as bycatch in fisheries and are considered threatened in some regions. In art and fashion, the legendary purple dye remains a symbol of elegance and authority.

Snails caught as bycatch, including Bolinus brandaris and Hexaplex trunculus, are appreciated as flavourful seafood in countries like France, Italy, Spain, and Portugal. In Spain, for example, they are known as cañaíllas and are served cooked in coastal cuisine.

On the other hand, murex snails, including those used in dye production, can also have negative ecological impacts. Stramonita haemastoma has become a serious pest for oyster beds in the USA (see above), while Bolinus brandaris has shown measurable effects on local mollusc communities, especially in areas where the species was introduced either deliberately or unintentionally by humans.

Common whelk (Buccinum undatum) off the Scottish coast. Picture: Jim Greenfield (iNaturalist). |

Whelks are carnivorous and also scavengers. They prey on bivalves by boring through their shells using the radula (rasping tongue), aided by a specialised gland in the foot that helps dissolve the calcium carbonate. Their diet is quite varied: they feed not only on bivalves, but also on crustaceans, sea urchins, and polychaete worms. Whelks are also known to follow starfish and feed on their prey, although this can be risky: some species, such as the spiny starfish (Marthasterias glacialis), which prefer molluscs as prey, can be dangerous to whelks themselves. The whelks' well-developed sense of smell, supported by a long siphon, helps them find both food and mates – as well as avoid predators.

Whelks are dioecious (having separate sexes), and mating occurs at different times of year depending on habitat. The female lays egg masses composed of thick-walled capsules, each of which may contain between 600 and 2000 eggs. However, only about 1% of the young snails actually hatch, having developed entirely within the capsule. The rest serve as food for their siblings. Some capsules are completely empty and function solely as added protection for the inhabited ones.

Hermit crabs (Pagurus bernhardus: Oosterschelde, Netherlands) often choose abandoned shells of whelks as new homes. Picture: Adrie Rolloos (iNaturalist). |

Whelks are ecologically important in the habitats where they occur. As predators, they help regulate other animal populations by targeting sick or injured individuals. As scavengers, they assist in breaking down dead organic matter. Their excretions contribute to nutrient cycling on the seafloor. And finally, their empty shells provide valuable habitat for other species – most famously, for hermit crabs like Pagurus bernhardus.

![]() Familie Buccinidae -

Wellhornschnecken. In: WIESE, V., JANKE,

K.: Die Meeresschnecken und -muscheln Deutschlands, S. 181 ff. Quelle & Meyer

Verlag 2021.

Familie Buccinidae -

Wellhornschnecken. In: WIESE, V., JANKE,

K.: Die Meeresschnecken und -muscheln Deutschlands, S. 181 ff. Quelle & Meyer

Verlag 2021.![]() Common Whelk (Buccinum undatum): Biology

and Ecology.

Common Whelk (Buccinum undatum): Biology

and Ecology.

In many coastal regions, the common whelk – once also known as the "kinkhorn" – has long been among the marine molluscs traditionally exploited by humans. While their shells were historically used as musical instruments, tools or trade goods, the snails themselves have served as a source of food since ancient times. Especially during the harsh winter months, whelks offered coastal communities a welcome supplement to their diet, as they were easy to catch or collect and could be preserved for longer periods.

This long-standing relationship is reflected in language: in most European languages, whelks have their own distinct names. In English, the term "whelks" is used for Buccinum undatum, but also for several similar species. In French, they are known as "boulots" or "buccins"; in the Netherlands, as "wulken"; and in Flanders, "karakollen" – likely a linguistic remnant of the region’s Spanish history.

Even today, whelks remain firmly rooted in the traditional cuisine of the North Atlantic region, though their preparation varies as widely as the names they go by. Whether served as whelks, boulots or wulken, they are still a common sight on fish markets. In Britain, they are a popular type of street food, typically served with vinegar from market stalls and seaside vendors – but they also feature as delicacies on the menus of high-end restaurants.

|

East Asian "Whelks"? Buccinum isaotakii: This species is native primarily to the cold waters surrounding Hokkaido (Japan). It is often sold fresh on local markets and served grilled or in soups. Neptunea arthritica: Also known as the "Japanese whelk", this species is found in the north-west Pacific (and has been introduced to the Black Sea). It is commonly served boiled, often as a snack with soy sauce.  "Asian whelk" (Rapana venosa, Muricidae) near Marseille. Picture: Frédéric André, iNaturalist.org. Rapana venosa: Although this species belongs to the murex family (Muricidae), it is frequently marketed as a “whelk”. Originally native to the Sea of Japan, it was transported to the European Atlantic coast and the Black Sea via shipping (ballast water). In China, it is considered a delicacy and typically served grilled or steamed. |

In recent years, however, interest in these versatile molluscs has spread far beyond Europe. In many East Asian countries such as Japan, Korea, and China, whelks are considered a delicacy. The family Buccinidae, to which the common whelk (Buccinum undatum) belongs, is also found in other parts of the world—for example, the genus Burnupena along the coast of South Africa. In East Asia, several species of Buccinum and similar genera such as Rapana and Neptunea (see box on the right) are native. Yet demand for whelks in these countries is so high that large quantities are imported from Europe.

![]() Whelks - scavengers that can drill into mussel shells!: Marine biologist

Prof. Charles Griffiths reports about the ecology of South-African whelks (Burnupena).

Whelks - scavengers that can drill into mussel shells!: Marine biologist

Prof. Charles Griffiths reports about the ecology of South-African whelks (Burnupena).

Whelks are not only a popular dish along the coasts of Europe, but are now enjoyed in many other parts of the world as well. In the UK, they are traditionally pickled in vinegar and sold at markets as "whelks in vinegar". In France, by contrast, they are considered a delicacy: There, they are served as bulots mayonnaise, boiled in salted water and accompanied by a spicy mayonnaise. This speciality is especially common at fish markets in Normandy and Brittany.

In Belgium, the snails are known as karakollen or wulken and are served hot at funfairs and street festivals, having been cooked in a hearty herb broth. Their intense, slightly salty flavour makes them a popular snack.

Whelks are also well-loved in Asia. In Korea, they are prepared as golbaengi muchim (골뱅이 무침), mixed with vegetables, spicy gochujang (chilli paste) and sesame oil, and served as a side dish with cold rice wine. In China, they are often found in soups and stews, while in Japan they are used as a soup ingredient or eaten raw as sashimi.

Whelks are increasingly finding their way into gourmet cuisine as well. One example of a modern development is the "whelk spring rolls" created by renowned seafood chef Rick Stein and his son Jack Stein: a fusion of Asian culinary technique and European tradition. Tender pieces of whelk are wrapped in pastry and deep-fried until crisp – a dish that is growing in popularity.

![]() Unsung Seafood:

Rick Stein tries Jack's Whelk Springrolls.

Unsung Seafood:

Rick Stein tries Jack's Whelk Springrolls.

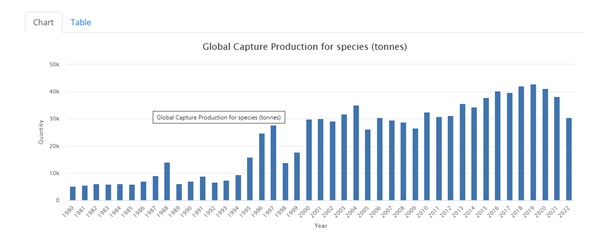

Global capture production of common whelks (Buccinum undatum). Source: FAO: Whelk (Buccinum undatum). |

![]() FAO: Whelk (Buccinum undatum): Website of the UN Food and

Agriculture Organization (FAO) with data on distribution and fishery numbers of

the common whelk.

FAO: Whelk (Buccinum undatum): Website of the UN Food and

Agriculture Organization (FAO) with data on distribution and fishery numbers of

the common whelk.

Most whelks caught are cleaned, cooked, and preserved in specialised processing facilities before being deep-frozen and shipped to Asia. There, they are either sold directly or further processed – often into canned or dried products.

As a result, increasing attention is being paid to the sustainable use of whelks and the protection of their natural populations, which play an important role in their ecosystems (see above). One potential way to ease pressure on wild stocks is through so-called aquaculture – the farming and cultivation of aquatic animals such as the common whelk.

One such project has been reported from Denmark, with similar farms now also established in France, Canada, the UK and Belgium.

![]() NIELSEN,

J.W., Rønfeldt, J.L. (2022): "Appraisal of a

novel fishery of whelks (Buccinum undatum) in Danish Waters". Regional

Studies in Marine Science 56. (Link).

NIELSEN,

J.W., Rønfeldt, J.L. (2022): "Appraisal of a

novel fishery of whelks (Buccinum undatum) in Danish Waters". Regional

Studies in Marine Science 56. (Link).

![]() CBC Kanada:

Commercial whelk fishery opens in eastern Cape Breton (Nova Scotia, Kanada).

CBC Kanada:

Commercial whelk fishery opens in eastern Cape Breton (Nova Scotia, Kanada).

![]() Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO), Canada:

Whelk (Buccinum undatum) ... Newfoundland and Labrador Region: Economic

whelk fishery on the Southern coast of Newfoundland.

Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO), Canada:

Whelk (Buccinum undatum) ... Newfoundland and Labrador Region: Economic

whelk fishery on the Southern coast of Newfoundland.

Although the common whelk is considered a resilient species, overfishing and environmentally harmful fishing practices have led to population declines in recent years. The use of dredges and bottom trawling in particular damages seabeds and thus negatively affects the natural habitats of whelks. In addition, whelks – like many other marine animals – are impacted by the general deterioration of water quality due to human activity, as well as by climate change.

As whelks are predators and scavengers, they also accumulate pollutants from their prey, making them more vulnerable to environmental toxins than herbivorous marine snails.

The United Kingdom was among the first countries to introduce conservation measures, including minimum landing sizes and restrictions on certain fishing techniques. The Netherlands and Ireland are also placing increasing emphasis on sustainable fisheries in order to preserve whelk populations in the long term.

![]() North Western Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority (NWIFCA)

(Großbritannien):

Managing sustainable fisheries: Shellfish: Whelk.

North Western Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority (NWIFCA)

(Großbritannien):

Managing sustainable fisheries: Shellfish: Whelk.

Periwinkles (Littorina littorea) during low tide. Picture: L. Packer (iNaturalist), Massachusetts, USA. |

Their muscular foot is particularly useful for life in the intertidal zone, allowing them, aided by sole mucus, to cling tightly to the often slippery surfaces of rocks, even in strong surf. Periwinkles feed primarily on algae growing on coastal rocks, which they graze using their radula (a rasping tongue-like organ). They are most active during high tide, when their feeding grounds are submerged.

Interestingly, periwinkles develop different feeding strategies depending on local conditions: on wave-exposed shores, they tend to graze firmly attached algae, while in more sheltered areas, they scrape soft algal films from the substrate.

Periwinkles have separate sexes. Mating usually occurs in spring, often synchronised with tidal cycles. After internal fertilisation, females lay small egg capsules in protected crevices. The eggs hatch into free-swimming veliger larvae that develop within the plankton before settling on the seabed and transforming into adult snails.

| & |

Periwinkles of the North and

Baltic Sea The following species of periwinkles (Littorinidae) occur at the North and Baltic Sea coasts: - Common periwinkle (Littorina littorea) - Flat periwinkle (Littorina obtusata) - Acute periwinkle (Melarhaphe neritoides) - Rock periwinkle (Littorina saxatilis). (see MolluscaBase eds. (2025). Littorinidae CHILDREN, 1834).  Common periwinkle (Littorina littorea), Maine, USA. Picture: Grace Shen, (iNaturalist). Preferred Habitats: - Melaraphe neritoides: Crevasses, splash zone. - Littorina saxatilis: Hard substrate, high tide zone. - Littorina obtusata: Tide pools, tide zone. - Littorina littorea: Hard substrate, max. 60m depth. |

![]() Wikipedia:

Littoral zone in oceanography and marine biology.

Wikipedia:

Littoral zone in oceanography and marine biology.

Along the coasts of the North and Baltic Seas, periwinkles are typical inhabitants of the intertidal zone. The most common species is the common or edible periwinkle (Littorina littorea), which can be found in vast populations on rocks, groynes, and among seagrass meadows. Another species, the small periwinkle (Melarhaphe neritoides), also inhabits this zone but prefers the higher areas of the intertidal range. It tends to cling to vertical rock faces and lives in crevices in the splash zone. Periwinkles are largely true to their living site, meaning they tend to remain in the same area. They orient themselves using the position of the sun to return to their original location.

![]() Familie Littorinidae

- Strandschnecken. In: WIESE, V., JANKE,

K.: Die Meeresschnecken und -muscheln Deutschlands, S. 98 ff. Quelle & Meyer

Verlag 2021.

Familie Littorinidae

- Strandschnecken. In: WIESE, V., JANKE,

K.: Die Meeresschnecken und -muscheln Deutschlands, S. 98 ff. Quelle & Meyer

Verlag 2021.

Periwinkles are also widely distributed along the European Atlantic coast, from Norway to Portugal. In those regions, they live on rocky coastal areas as well as in salt marshes and estuaries, where they have perfectly adapted to tidal change.

On the North American Eastern coast especially the common periwinkle (Littorina littorea) and the rock periwinkle (Littorina saxatilis) are present. The common periwinkle is especially considered an invasive species there, since the species has probably been introduced to the area by ships from Europe in the 19th century. Until today it has spread along all of the coast as far as Canada and is even used economically.

Common periwinkle (Littorina littorea) grazing algae growth. Picture: Matreks (iNaturalist), Norway. |

In seagrass meadows, periwinkles are of great ecological importance, as well: By feeding on the algae that grow on seagrass leaves, they support the health and growth of the seagrass itself. Seagrass meadows, in turn, are among the most valuable marine ecosystems, serving as a habitat for many species and providing a large amount of the world's oxygen.

For this reason, periwinkles are sometimes referred to as "gardeners of the intertidal zone".

![]() NABU:

Putzkolonne für Seegraswiesen: Strandschnecken (Littorinidae spp.). (In

German).

NABU:

Putzkolonne für Seegraswiesen: Strandschnecken (Littorinidae spp.). (In

German).

Due to their high population density, periwinkles also influence other organisms: The areas they clear through grazing provide space for the settlement of new algae and microorganisms. At the same time, periwinkles constitute an important food source for many coastal birds, fish, and crabs. Even their shells are reused after death: hermit crabs, such as the long-clawed hermit crab (Pagurus longicarpus), often inhabit them. Originally native to the eastern coast of North America, this crab species has now been introduced to the North Sea via ship ballast water, where it was first recorded in 2022.

![]() NEUMANN,

H., KNEBELSBERGER, T., BARCO,

A., HASLOB, H. (2022): First record and spread

of the long-wristed hermit crab Pagurus longicarpus SAY,

1817 in the North Frisian Wadden Sea (Germany). BioInvasions Records 11/2, pp.

482–494 (PDF).

NEUMANN,

H., KNEBELSBERGER, T., BARCO,

A., HASLOB, H. (2022): First record and spread

of the long-wristed hermit crab Pagurus longicarpus SAY,

1817 in the North Frisian Wadden Sea (Germany). BioInvasions Records 11/2, pp.

482–494 (PDF).

![]() BLACKSTONE,

N.W., JOSLYN, A.R. (1984): Utilization and

preference for the introduced gastropod Littorina littorea (L.) by the

hermit crab Pagurus longicarpus (SAY)

at Guilford, Connecticut. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology

80/1, pp. 1-9 (Abstract).

BLACKSTONE,

N.W., JOSLYN, A.R. (1984): Utilization and

preference for the introduced gastropod Littorina littorea (L.) by the

hermit crab Pagurus longicarpus (SAY)

at Guilford, Connecticut. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology

80/1, pp. 1-9 (Abstract).

Because they live in direct contact with the water and absorb pollutants through their diet, the population size and health of periwinkles reflect the condition of their habitats. They are therefore considered valuable bioindicators of environmental change. In the North and Baltic Seas, periwinkle populations are regularly monitored to provide insight into pollution levels, temperature changes, and ocean acidification. Like whelks, periwinkles have also been affected by marine pollution, especially from TBT (tributyl tin).

In today's Baltic Sea area, the common periwinkle (Littorina littorea) even serves as a type fossil: The so-called Littorina Sea, which formed around 7,000 years ago in what is now the Baltic basin, was named after this species. During that period, salty seawater from the Atlantic flooded into the previously freshwater-filled basin. This event, known as the Littorina transgression, had profound effects on local ecosystems and human settlement patterns. It is named after fossil evidence of Littorina littorea, which appeared suddenly and abundantly in deposits from that time.

![]() Wikipedia:

The Littorina Sea.

Wikipedia:

The Littorina Sea.

![]() RÖSSLER,

D. (2006): Reconstruction of the Littorina Transgression in the Western Baltic

Sea. Meereswissenschaftliche Berichte, Nr. 67. Institut für Ostseeforschung. (PDF).

RÖSSLER,

D. (2006): Reconstruction of the Littorina Transgression in the Western Baltic

Sea. Meereswissenschaftliche Berichte, Nr. 67. Institut für Ostseeforschung. (PDF).

Edible periwinkle (Littorina littorea) during low tide. Picture: jsep1 (iNaturalist), Massachusetts, USA. |

![]() Wikipedia:

Bigorneaux perceurs (In French).

Wikipedia:

Bigorneaux perceurs (In French).

![]() Wikipedia:

Autres noms vernaculaires (In French).

Wikipedia:

Autres noms vernaculaires (In French).

Periwinkles (caracolillos) in a restaurant in Spain. Picture: L'irlandés (Wikipedia). |

In France, periwinkles are a regular part of the famous plateaux de fruits de mer (seafood platters) offered at markets and restaurants. Cooked periwinkles are also commonly found at weekly markets in Belgium and the Netherlands, particularly in harbour towns, where they are freshly prepared and sold as a popular snack.

Traditionally, periwinkles are collected by hand or using small traps placed among rocks and seaweed. In recent years, sustainability measures have been introduced to prevent overfishing and protect periwinkle stocks. In France, it is still common to collect periwinkles while walking along the shore and to cook them fresh at home — a tradition that forms part of local coastal life.

![]() La pêche des bigorneaux (In French): describes the traditional pastime of

gathering periwinkles along the French coast.

La pêche des bigorneaux (In French): describes the traditional pastime of

gathering periwinkles along the French coast.

In Cantabria, northern

Spain, periwinkles have a particularly long culinary history. In the cave of

Altamira on Spain’s northern coast, fossilised shell remains suggest that people

were already harvesting periwinkles there 15,000 years ago.

![]() Wikipedia:

Littorina littorea - Utilisation (In French).

Wikipedia:

Littorina littorea - Utilisation (In French).

Even today, "caracolillos", as they are known in northern Spain, remain a staple of the local cuisine. They are usually boiled in salted water and served with a simple but flavourful sauce. In the ports of Galicia or the bays of the Basque Country, periwinkles are commonly sold alongside other shellfish such as mussels and cockles, especially during traditional festivals.

The historic trade in periwinkles also flourished: at the Mercado de la Ribera in Bilbao, Spain’s largest covered market, periwinkles were already being traded in the 19th century. Fishermen brought them from the coastal waters of Cantabria and Galicia, often preserved in barrels to keep them fresh longer. In the narrow streets surrounding the market, they were cooked in large pots.

In Bilbao, it became popular to serve the snails with a rich garlic sauce or a spicy tomato marinade—dishes that are still part of the city’s gastronomic heritage today, especially during the Semana Grande (Aste Nagusia) celebrations, where the dish is freshly prepared in the old town.

In a similar way, a lively historical trade once existed in Central Europe

for the edible Roman snail (Helix pomatia), which were transported from

Swabia to Vienna: (![]() History of Snail Farming).

History of Snail Farming).

Periwinkles are not only a culinary delicacy in many coastal regions but also of economic significance. In France, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the UK, they form an integral part of the seafood market. Traditionally, the snails are collected by hand, especially during low tide when they are easily accessible in tidal pools and on rocky shores. In some areas, special traps or baskets are also used, set out among the rocks to catch the snails. The periwinkles are then often sold at market stalls in small nets or baskets.

The highest demand for periwinkles comes from France and the UK. Interestingly, a portion of the snails caught in Britain is also exported to Asia, where they are considered a delicacy—particularly in South Korea and Japan, where periwinkles are preserved and sold in tins as a snack. Processing for export usually takes place in the coastal regions, where the snails are cleaned, pre-cooked, and then either deep-frozen or canned for shipping. Thanks to these preservation methods, they are available even outside of the harvesting season and can be traded globally.

In recent years, the sustainability of periwinkle harvesting has become more regulated. In the UK and Ireland, quotas and minimum size limits have been introduced to protect wild stocks. France has also implemented strict rules to prevent overfishing. These measures became necessary as demand increased sharply over the past decades, and overexploitation had already begun to affect some regions. Today, research is being carried out into periwinkle farming and sustainable management to help ensure the long-term viability of their populations.

|

What Are Abalones? The expression "Abalone" originates from the indigenous inhabitants of today's California. The Spanish changed it into "abulón", which in English led to the expression "Abalone".  Abalone (Haliotis asinina), Heron Island, Queensland, Australia. Picture: Pete Woodall, (iNaturalist). Due to their ear-shaped shells, those snails may also be referred to as sea-ear-shells. |

The shells of abalones are remarkably flat and ear-shaped due to their greatly enlarged final whorl. Along the outer edge of the shell runs a row of small perforations, which serve to expel respiratory water and waste products from the mantle cavity.

Shell view (Upper and lower side) of an abalone (Haliotis asinina). Right: Enlarged view of the shell spire. Picture: H. Zell (Wikipedia), modified. |

Some species of abalone, such as Haliotis gigantea, are even capable of producing pearls, a trait usually associated with certain bivalves.

Abalones live mainly on rocky substrates, where they use their large, muscular foot to cling tightly to the surface. This makes it very difficult for predators, including sea stars, octopuses, certain fish, and of course humans, to dislodge them, much like with limpets (Patellidae).

Their main food source is algae, which they graze from rocks using their rasping tongue, the radula. Through this feeding behaviour, they help to keep underwater vegetation in balance and play an important role in the health and stability of marine ecosystems.

![]() Wikipedia:

Haliotis.

Wikipedia:

Haliotis.

![]() Peter Haffner: "Schnecken

mit Schrecken - Abalone-Fischen in Kalifornien". Mare 98 (2013) (in German).

Peter Haffner: "Schnecken

mit Schrecken - Abalone-Fischen in Kalifornien". Mare 98 (2013) (in German).

![]() Dustin Lemick: "The

Science of Pearls: How Mollusks Make Jewelry". Brite.co, June, 2025.

Dustin Lemick: "The

Science of Pearls: How Mollusks Make Jewelry". Brite.co, June, 2025.

Abalones reproduce through external fertilisation: males and females release sperm and eggs into the surrounding water, where fertilisation occurs. Some species, like the red abalone, are particularly prolific: a single female may release over 12 million eggs. The larvae develop planktonically, passing through several stages (including the trochophore and veliger larval stages), before settling on suitable substrates and metamorphosing into juvenile snails.

![]() WILSON,

N.H.F. & SCHIEL, D.R. (1995): Reproduction on

two species of abalone (Haliotis iris and H. australis) in

southern New Zealand. Marine and Freshwater Research 46(3), pp. 629 - 637. (Abstract).

WILSON,

N.H.F. & SCHIEL, D.R. (1995): Reproduction on

two species of abalone (Haliotis iris and H. australis) in

southern New Zealand. Marine and Freshwater Research 46(3), pp. 629 - 637. (Abstract).

![]() Joshua Williams and

Sarah Yesil:

Haliotis fulgens on

Animal Diversity Web.

Joshua Williams and

Sarah Yesil:

Haliotis fulgens on

Animal Diversity Web.

![]() Wikipedia:

Haliotis asinina: Life Cycle.

Wikipedia:

Haliotis asinina: Life Cycle.

"Pāua" (Haliotis iris) can hardly be distinguished from their surroundings in nature. Picture: Kevin Frank (iNaturalist), Wellington, NZ. |

Particularly large populations of red abalone (Haliotis rufescens) occur along the west coast of the United States and Mexico. California is considered one of the historical centres of abalone fishing. Japan, South Korea, and China operate extensive aquaculture systems for the commercial production of abalones. Australia and New Zealand also host abundant species, including the blacklip abalone (Haliotis rubra) and the iconic pāua (Haliotis iris), which is especially prized by the indigenous Māori people of New Zealand for its vividly coloured mother-of-pearl.

South Africa is home to some of the rarest and most valuable abalone species. Most notably, the endemic Haliotis midae, known locally in Afrikaans as perlemoen, is cultivated in sustainable aquaculture farms. However, wild populations have become highly endangered due to overfishing.

"Pāua" (Haliotis iris) are favoured art objects among the Māori people. Picture: Peter de Lange (iNaturalist), Kapiti Island, NZ. |

Abalones favour rocky coastal habitats, where they seek shelter in crevices and under ledges. They are often found in the intertidal zone, where they graze on algae. Juveniles tend to settle in shallower waters, while older individuals may live at depths of 20 to 30 metres.

These snails are consequently true to their location, rarely leaving their chosen habitat unless displaced by strong currents or storms. This fidelity to a specific location also makes them particularly vulnerable to environmental changes, pollution, and overexploitation.

Abalones play a vital role in marine ecosystems. As specialised grazers, they feed on various algae, particularly macroalgae such as seaweed and kelp. Through their grazing activity, they help regulate algal growth, preventing the overgrowth of coral reefs and other marine habitats. In areas with stable abalone populations, kelp forests often develop—these provide habitat and food for countless marine species. By clearing patches of rock through grazing, abalones also facilitate the settlement of new algae and provide surfaces for other marine organisms to colonise. Haliotis rufescens, found along the west coast of the United States, is especially important for maintaining the stability of such ecosystems.

Beyond their ecological functions, abalones are also an essential part of the marine food web. They serve as prey for a variety of marine predators, including octopuses, sea stars, lobsters, and certain fish species such as wrasses (Labridae). In Australia and New Zealand, pāua (Haliotis iris) are a common target for lobster populations.

Due to their strong living grounds fidelity, abalones are highly sensitive to environmental changes, particularly those caused by pollution, overfishing, and climate change. Their populations are therefore a valuable indicator of marine ecosystem health. In regions suffering from high levels of water pollution, abalone numbers decline rapidly - this in turn disrupts the balance of algal communities and affects overall biodiversity.

![]() Wikipedia:

Haliotis: Conservation.

Wikipedia:

Haliotis: Conservation.

Abalones are considered an exquisite delicacy in many parts of the world. Especially in Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, they are highly prized and associated with luxury and fine dining. The preparation of abalone is a refined art that is often passed down through generations.

Tokobushi Sashimi in a Japanese restaurant. Source: Wikipedia. |

Tokobushi (トコブシ), a term for Haliotis diversicolor in Japan, is often also listed under the obsolete name Sulculus diversicolor supertexta. As domestic stocks of this species, ranging from Hokkaido to Kyushu, are insufficient to meet Japanese demand, larger quantities are imported from Taiwan and China, or a closely related species (Haliotis glabra GMELIN 1791) from the Philippines.

![]() Sushiuniversity.jp:

What is tokobushi abalone sushi?.

Sushiuniversity.jp:

What is tokobushi abalone sushi?.

![]() WoRMS: MolluscaBase eds. (2025):

Haliotis diversicolor REEVE, 1846.

WoRMS: MolluscaBase eds. (2025):

Haliotis diversicolor REEVE, 1846.

Because of their slow growth and high demand, abalones are now regarded as a luxury item. Freshly harvested specimens can fetch premium prices on the global market and are served as rare delicacies in gourmet restaurants. The consumption of abalones caught from the wild is strictly regulated or even banned in many areas to protect natural populations. As a result, aquaculture is increasingly used to meet demand while preserving wild stocks.

The economic importance of abalones extends far beyond the kitchen. Their high market value makes abalone farms some of the most lucrative aquaculture ventures in Asia, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the USA. Due to heavy exploitation and environmental changes, wild populations have drastically declined in many regions. Aquaculture has therefore emerged as a sustainable alternative:

In parts of Europe, the green ormer (Haliotis tuberculata) is also harvested for seafood. "Ormering" – named after the English term green ormer – is a traditional pastime on the Channel Islands (Jersey, Guernsey, and Alderney), comparable to gathering periwinkles in northern France. However, due to ecological degradation of the North Sea and English Channel, and because of past overfishing, green ormers have become rare in some areas. As a result, harvesting on the Channel Islands is now strictly regulated.

Green ormer (Haliotis tuberculata): Lanzarote, Canary Islands. Picture: Oscar Sampedro (iNaturalist). |

Māori engraving with eyes made from Pāua (Haliotis iris). Picture: James Shook (Wikipedia). |

|

Due to high demand and limited supply, a lucrative black market for abalone has developed in recent decades. Illegal harvesting, often controlled by organised crime groups, is especially widespread in South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. The stolen catches are frequently smuggled to China, where they are sold at high prices as a luxury delicacy. Overfishing and poaching have caused dramatic population declines in some regions, particularly affecting the perlemoen (Haliotis midae) in South Africa, the blacklip abalone (Haliotis rubra) in Australia, and the pāua (Haliotis iris) in New Zealand.

![]() Wikipedia:

Abalone fishing in South Africa.

Wikipedia:

Abalone fishing in South Africa.

![]() Wikipedia:

Pāua: Harvesting.

Wikipedia:

Pāua: Harvesting.

The Chumash, an Indigenous people of California, used abalone shells as a form of currency. Small, flat beads were cut and polished from the shell’s mother-of-pearl layer and then strung together. These bead strings were used in trade and had values that varied depending on their size and lustre. Other Indigenous groups along the west coast of North America, such as the Pomo and the Wiyot, also used abalone shells as a medium of exchange. The beads were considered more valuable than whole shells and were traded for tools, food, or ornaments.

Much like cowrie shells (Cypraeidae, e.g. Monetaria moneta), which served as currency in Africa, Asia, and Oceania, abalone shells fulfilled a similar function in the Pacific region. While cowries were favoured for their small, stable shape and used like coins, abalone beads were strung in long strands that denoted their value.

Both forms of shell currency held deep cultural significance. Cowries were associated with fertility and wealth, whereas abalone shells symbolised prosperity, protection, and a strong connection to the coast among Native American communities.

Latest Change: 22.10.2025 (Robert Nordsieck).