| Diese Seite auf Deutsch! |

The History of Snail Cultivation |

The "Roman" snail (Helix pomatia). Picture: Robert Nordsieck. |

The history of snail farming is as twisted as the shells of the creatures themselves – from prehistoric food waste to Roman delicacy gardens, from Swabian snail plots to modern gourmet farms. For thousands of years, humans have collected, kept and enjoyed snails – whether out of necessity, religious tradition, or culinary pleasure.

Over time, regional centres of snail use emerged: the Romans cultivated cochlearia, monasteries bred snails as Lenten fare, Swabian farmers delivered snails in barrels along the Danube as far as Vienna, and today gourmet chefs are experimenting with innovative recipes using farmed snails.

This page explores the varied and curious history of snail consumption – from the Stone Age to the Slow Food movement of the 21st century. It’s a story not only of food, but also of economy, religion, regional identity and cultural heritage – and, not least, of the quiet comeback of a much-underestimated mollusc.

|

Plinius I., Naturalis Historia Book 9:78: Shortly before the war between Caesar and Pompey Fulvius Hirpinus built snail parks near Tarquinii. He distin guished the snails in classes by keeping them separated: – the white snails from the region of Reate – those from Illyria which were the largest, – those from Africa which bred the most, – and those from Solitum which were most sought after. He even invented a method to fatten them, with wine boiled up, flour and other food, so that the fattened snails would give the goumet additional pleasure. |

Plinius the Elder (23 - 79 v. Chr.). |

![]() Wikipedia:

Snails as Food: History.

Wikipedia:

Snails as Food: History.

![]() Wikipedia:

Midden.

Wikipedia:

Midden.

![]() Glyptodon:

Prehistoric Greek Snail Farmers.

Glyptodon:

Prehistoric Greek Snail Farmers.

In antiquity, the use of snails became more systematic. The Romans were likely the first to not only collect snails but to breed them deliberately. They called the animals cochleae: a word also used for a ladle, named after the spiralled shape of the shell. In special snail gardens, known as cochlearia, land snails such as Helix pomatia and its relatives were fattened with milk or flour before being served as a delicacy. Writers such as Varro and later Pliny the Elder mention such practices and praised the supposed aphrodisiac qualities of the animals.

As the Roman Empire expanded, it spread not only culinary traditions, but also snail species themselves. The brown garden snail (Cornu aspersum) was carried far beyond its native Mediterranean range – possibly already by Phoenicians and Greeks, but certainly by Roman soldiers who brought snails as a convenient source of food. Archaeological finds of Helix shells in latrines and kitchen waste have confirmed snail consumption throughout the Empire – even in Britain, where Helix pomatia is still known as the "Roman snail".

At the same time, the gradual deforestation of Central Europe by Celts and Germanic peoples during the Iron Age created the kind of woodland edge habitats that Helix pomatia and similar species thrive in. These transitional environments remain ideal for many land snails to this day.

Snail trader in Indelhausen, Lauter Valley. |

With the rise of Christianity in Europe, the perception of snails – particularly their culinary use – began to change. Since they were considered neither meat nor fish, they were classified as acceptable food during periods of fasting. Thus, the Roman snail (Helix pomatia) became something of a delicacy within monastery walls – often accompanied by a good beer. Many medieval monasteries maintained their own snail gardens, where the animals were kept and fattened up for consumption. It is even said that Pope Pius V (1505–1572), a great lover of snails, once declared: “Estote pisces in aeternum!” ("May you be fish for all eternity!"), meaning that snails were henceforth to be considered fish – and therefore permitted during Lent.

But it wasn’t only monks who appreciated these humble molluscs. Snails were also seen as a "poor man’s food" in many regions: nutritious, easy to gather, and entirely free – a welcome addition to the diet at a time when meat was expensive and often reserved for the nobility. In southern Germany, particularly in the Lauter Valley on the Swabian Jura, early forms of snail farming emerged, with animals kept in enclosed gardens.

Historical snail garden built by the Nürtingen University of Applied Sciences as part of the Albschneck project. |

|

Closed-up lid snails ready for trade. Picture: Monika Samland, Dt. Institut für Schneckenzucht. |

![]() Hibernation of the Roman Snail (Helix pomatia).

Hibernation of the Roman Snail (Helix pomatia).

As a result, snail breeding gained importance. While wild collection and fattening-up might suffice for home use, those who sold snails at market began selecting the largest and tastiest individuals. As early as the Middle Ages, snails were being fed aromatic herbs – an early form of culinary refinement.

Snails were also valued for their medicinal properties: in traditional folk medicine, snail-based remedies were used to treat coughs and consumption, most notably in the form of syrup made from snail slime.

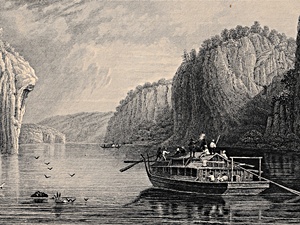

Ulm box boat near Kellheim (Danube). Engraving (1839), |

From here, the Swabian snail began its eastward journey. The snails were first brought to the city of Ulm, where they were packed into large barrels and loaded onto so-called Ulmer Schachteln (Ulm box boats) – flat-bottomed river barges that sailed down the Danube all the way to Vienna. These "fat lid-snails" (Helix pomatia, for the most part), ideal for transport thanks to their sturdy hibernation seals, became a popular Lenten dish in the monasteries along the river – and eventually reached the imperial court of the Habsburgs.

The trade in snails flourished: at times, up to 500 tonnes of snails were shipped each year. According to legend, the Swabian merchants would return home on foot – often accompanied by children fathered during their time in Vienna. It’s no surprise, then, that the locals jokingly referred to their product as "snails with a Maultasche diploma", Maultaschen being a traditional Swabian dish.

Even Napoleon is said to have carried snails with him on campaign, considering them a nutritious "natural preserve". And business was booming in the French capital as well: as late as 1908, the tiny village of Guttenstein in the Swabian Jura exported a remarkable four million snails to Paris – at a going rate of four to five marks per thousand.

But with the advent of modern preservation techniques, the golden age of Swabian snail trading came to a slow end. Snails began to disappear from market stalls – only to reappear later on, gracing the menus of gourmet restaurants.

Farm smail among clover plants. Picture: Robert Nordsieck. |

In south-eastern Europe, however – in countries such as Bulgaria and Turkey – edible snails are still commonly collected from the wild. In Turkey, this often involves the banded Roman snail (Helix lucorum), which is a typical export product for European markets. In Italy, the smaller and more pungent green snail (Cantareus apertus) is popular in regional cuisine.

Enclosures on a snail farm in Elgg (Switzerland). Picture: Robert Nordsieck. |

In rural parts of central Europe, some farms and traditional inns are rediscovering the old snail culture. From Styria to the Swabian Jura, snails are once again appearing on menus – whether as modern reinterpretations or as hearty "snail dumplings with horseradish and cabbage", as once served in the 18th and 19th centuries. While some farms rely on traditional methods, others pursue modern production techniques in hopes of higher yields. Many newcomers to snail farming, however, have learned the hard way that this is not a quick-profit venture: it can take up to three years for a snail farm to become profitable. Even then, outdoor farming remains vulnerable to weather, predators, and other unpredictable factors.

In the Austrian state of Styria, there’s a saying that snails are "good for male virility". Whether there’s any medical truth to that remains debatable – but clearly, it hasn’t hurt the popularity of the delicate morsels.

And who would have guessed that the Slow Food movement would choose the snail as its emblem? Perhaps because it stands for regionality, quality – and for a good life, lived without haste. And from an ecological point of view, snail farming also has its appeal: snails require up to 85% less biomass to produce edible protein than cattle or pigs.

![]() Map of the Snail

Farms in Germany and Austria.

Map of the Snail

Farms in Germany and Austria.

Even though industrial snail farming is now globally interconnected, there are still regions where a particularly rich snail tradition has been preserved – whether for culinary, geographical, or simply passionate reasons.

In the German federal state of Baden-Württemberg, especially on the Swabian Jura, the tradition of snail farming remains alive to this day. Here, it’s not only historical roots that are nurtured, but also new approaches:

Austria, too, has developed a vibrant snail scene:

These regional distinctions show that snail farming is still very much alive – whether as a source of income, a cultural heritage, or a culinary passion. And who knows – perhaps you’ll come across it again soon… at a market stall, in a country inn, or even in your own back garden.

Latest Change:

03.07.2025 (Robert

Nordsieck).