| Diese Seite auf Deutsch! |

|

|

|

The common whelk (Buccinum undatum) is a large predatory sea snail found in cold and temperate waters of the North Atlantic, including the North Sea and parts of the western Baltic. It belongs to the family Buccinidae, known for their thick, spirally coiled shells and carnivorous lifestyle. With its robust shell and distinctive waved sculpture, the common whelk is well adapted to life in subtidal and deeper coastal zones, where it plays an important ecological role as both predator and scavenger. It is also of considerable economic importance in many northern countries, where it is harvested for food and traded internationally.

![]() Taxonomy of Gastropoda:

Clade Caenogastropoda: Buccinidae.

Taxonomy of Gastropoda:

Clade Caenogastropoda: Buccinidae.

![]() Whelks - scavengers that can drill into mussel shells!: Marine biologist

Prof. Charles Griffiths speaks about the life and ecology of South-African

whelks (Burnupena).

Whelks - scavengers that can drill into mussel shells!: Marine biologist

Prof. Charles Griffiths speaks about the life and ecology of South-African

whelks (Burnupena).

The common whelk is widely spread along the Atlantic coast from North America as far as Greenland, as well as in Europe from Norway to Brittany. It is usually found in shallow coastal waters, but can live as deep as 200 metres (~ 600 ft.). It usually prefers sandy or muddy substrates, where it stays burrowed in the ground during the day and goes out hunting during the night.

Common whelk (Buccinum undatum) off the Scottish coast. Picture: Jim Greenfield (iNaturalist). |

|

A common whelk's (Buccinum undatum) sipho is not only used to provide the snail with breathing water, but with a means to orient for food, other whelks or enemies. Picture: Peter Jonas, Unterwasser-Welt Ostsee. |

![]() Wikipedia:

Buccinum undatum.

Wikipedia:

Buccinum undatum.

![]() MarLIN UK:

Common Whelk (Buccinum undatum).

MarLIN UK:

Common Whelk (Buccinum undatum).

The common whelk (Buccinum undatum) has a sturdy, spirally coiled shell with typically 7 to 8 whorls. Shell coloration ranges from pale yellow to brownish-grey, often with darker bands or spots. The surface is prominently ridged, which strengthens the shell and helps the whelk withstand currents in the North Atlantic and North Sea.

The shell aperture is large and oval, featuring a distinct siphonal canal through which the snail, by way of its siphon, an elongated funnel emerging from the mantle, is provided with breathing water. On one hand, this allows the snail to obtain oxygen, on the other the snail is able to detect chemical cues in the water. Specialized chemosensory organs in the mantle cavity, called osphradia, help the whelk locate food, find mates, and avoid predators. Using its siphon, the snail can determine the direction of such chemical signals.

As in all gastropods, the soft body consists of a head, a muscular foot, and a visceral mass or visceral sack, covered by mantle tissue and completely enclosed within the shell. When it is active, the whelk extends its head and foot; at the head are two tentacles that cannot be retracted, with eyes situated at their base - unlike most land snails, which carry their eyes at the tips of their tentacles.

The whelk feeds using a typical gastropod radula - a ribbon-like tongue covered in rows of chitinous teeth - to rasp and tear food such as bivalves or carrion (see below).

The muscular foot is used not only for locomotion but also to help the snail keep its position in the sediment of the intertidal zone. The whelk even make use of its foot to subdue bivalves (see below). At the rear end of the foot is the operculum, a horn-like protective plate that closes off the shell aperture when the animal retreats into its shell, providing an effective defense against predators.

A common whelk (Buccinum undatum) laying eggs. Picture: Ron Offermans. |

When reproduction takes place, depends on the water's temperature: in colder northern waters, mating happens in spring when temperatures begin to rise, while in warmer European seas, mating takes place in autumn, as the water temperatures are cooler then and more favourable for the development of the young. During this time, the female releases pheromones to attract a mate.

Fertilisation takes place internally, which allows for the formation of protective egg capsules. These characteristic, balloon-shaped capsules are deposited by the female onto rocks or other hard substrates. Each capsule contains between 600 and 2000 eggs. Interestingly, the developing embryos within a single capsule may have different fathers, as female whelks can mate multiple times and store sperm until environmental conditions are optimal for egg-laying.

However, only a small number of juveniles will actually hatch. The others serve as a first food source for their older, more developed siblings. This type of development, in which the veliger larvae undergo their entire development within the capsule and hatch as miniature snails, is referred to as direct development - no free-swimming larval stage occurs. Some capsules may even be completely empty, serving only to protect the more centrally located capsules and the juveniles within.

![]() SMITH,

K.E. & THATJE, S. (2013): Nurse egg consumption

and intracapsular development in the common whelk Buccinum undatum

(Linnaeus 1758). Helgoland Marine Research 67 (1), 109-120. (Abstract).

SMITH,

K.E. & THATJE, S. (2013): Nurse egg consumption

and intracapsular development in the common whelk Buccinum undatum

(Linnaeus 1758). Helgoland Marine Research 67 (1), 109-120. (Abstract).

The young whelks hatch after about five to six months, measuring just 3-4 mm in length. They begin feeding immediately, but grow relatively slowly: sexual maturity is usually reached only after about five years. If undisturbed by human influence, the life expectancy of acommon whelk is approximately 10 to 15 years.

|

"Keep Your Valve Shut And You Might Live!" Bivalves are remarkably good at detecting the presence of a common whelk. Mobile species such as scallops (Pectinidae) or razor clams (Pharidae) will attempt to flee as soon as a whelk is detected nearby.  Blue mussels with barnacles. Picture: Keith Hiscock, MarLIN. Sessile species like blue mussels (Mytilidae), on the other hand, respond by keeping their shell tightly closed for as long as the whelk remains in the vicinity. |

Other marine gastropods, whose shell opening (aperture) is protected by an operculum (sometimes even other whelks), are attacked in a special way: the whelk drills through the shell wall of its prey using its radula. The drilling process is assisted by an acidic secretion produced by a special gland in its foot, which helps to dissolve the calcareous shell. Once the hole is complete, the soft body of the prey is consumed without resistance.

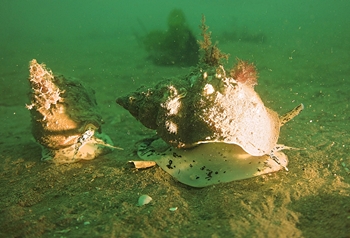

When subduing bivalves, whelks apply a different technique: they use their strong muscular foot to pull the shell valves apart. Sometimes, they even wedge the rim of their own sturdy shell between the valves like a lever. Once the valves are forced open, the bivalve is eaten quickly and efficiently. In fact, Buccinum undatum is surprisingly fast for a snail - a 2.5 cm cockle (Cardium edule) can be devoured in just 10 to 20 minutes.

Whelks also readily feed on carrion: groups of them are often found around fish waste on the sea floor. They may even follow sea stars to scavenge leftovers from their prey - often bivalves - or sift through the sediment the sea star dug up in search of food.

![]() HIMMELMAN,

J. H. & HAMEL, J.R. (1993): Diet,

behaviour and reproduction of the whelk Buccinum undatum in the

northern Gulf of St. Lawrence, eastern Canada. Marine Biology 116:3, pp.

423-430. (Abstract).

HIMMELMAN,

J. H. & HAMEL, J.R. (1993): Diet,

behaviour and reproduction of the whelk Buccinum undatum in the

northern Gulf of St. Lawrence, eastern Canada. Marine Biology 116:3, pp.

423-430. (Abstract).

![]() TAYLOR,

J.D. (1978): The diet of Buccinum undatum and Neptunea

antiqua (Gastropoda: Buccinidae). Journal of Conchology 29, p. 309. (Abstract).

TAYLOR,

J.D. (1978): The diet of Buccinum undatum and Neptunea

antiqua (Gastropoda: Buccinidae). Journal of Conchology 29, p. 309. (Abstract).

![]() PRICE,

N.R., HUNT, S. (1976): An unusual type of

secretory cell in the ventral pedal gland of the gastropod mollusc Buccinum

undatum L.. Tissue and Cell 8/2, pp. 217-228. (Abstract).

PRICE,

N.R., HUNT, S. (1976): An unusual type of

secretory cell in the ventral pedal gland of the gastropod mollusc Buccinum

undatum L.. Tissue and Cell 8/2, pp. 217-228. (Abstract).

Two whelks (Buccinum undatum) on the British southern coast. Picture: Tamsyn Mann (iNaturalist). |

![]() MarLIN UK:

Common Whelk (Buccinum undatum).

MarLIN UK:

Common Whelk (Buccinum undatum).

Whelks prefer sandy or muddy substrates near coastal areas but can also be found on rocky bottoms. They are most commonly found at depths between 10 and 200 metres, although specimens have been recorded from depths greater than 500 metres. In intertidal zones, they are rarely encountered, as they favour stable water temperatures and do not tolerate large thermal fluctuations well. Interestingly, juveniles and adults tend to inhabit different depths: younger whelks prefer shallower waters, while older individuals tend to migrate into deeper areas.

![]() Wattwandern mit Johann:

Dit un dat: Die Wellhornschnecke (In German).

Wattwandern mit Johann:

Dit un dat: Die Wellhornschnecke (In German).

Due to their relatively high salinity tolerance, common whelks can also survive in environments with fluctuating salt levels, such as fjords and estuaries. However, they prefer cold waters with salinities between 2 and 3%, and are rarely found in brackish areas with low salt concentrations.

Because of their affinity for cold water, common whelks are increasingly affected by rising ocean temperatures. In the southern parts of their range, populations have been declining in recent years, while in northern regions - such as along the coasts of Norway and Iceland - their numbers remain stable or even show signs of growth.

This whelk's shell lid (operculum) is well visible: Nova Scotia, Canada. Picture: Ian Manning (iNaturalist). |

Interestingly, whelks are capable of detecting weakened or injured animals by means of chemical signals in the water. Their osphradia - specialised chemoreceptors in the mantle cavity - allow them to locate prey precisely, ensuring that sick or damaged individuals are removed more quickly. This behaviour contributes to the overall health of marine populations.

Hermit crabs (Pagurus bernhardus: Oosterschelde, Netherlands) often choose the left-over shells of whelks as a new home. Picture: Adrie Rolloos (iNaturalist). |

In turn, whelks themselves are an important food source for various predators, including wading birds such as the oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus), as well as for certain fish and crustaceans. Even starfish prey on whelks: for instance, the spiny starfish (Marthasterias glacialis) feeds on mussels, other starfish, and also gastropods such as whelks. Since whelks have been observed to follow starfish to scavenge leftovers (see above), they must distinguish between harmless and predatory species using chemical cues like saponins to avoid becoming prey themselves.

![]() Animal Diversity Web:

Buccinum undatum.

Animal Diversity Web:

Buccinum undatum.

Even after a whelk's death, their empty shells continue to contribute to biodiversity: They serve as valuable new homes for hermit crabs (e.g. Pagurus bernhardus) and other small benthic organisms, offering protection from predators and environmental stress.

![]() Schutzstation Wattenmeer: "Wo

ist Bernhard?" (In German).

Schutzstation Wattenmeer: "Wo

ist Bernhard?" (In German).

|

Imposex: When Females Become Males Imposex is a form of sexual disruption in marine snails caused by environmental pollutants, most notably the organotin compound tributyl tin (TBT). Affected females develop male sexual characteristics such as a penis and vas deferens, which can severely impair or even completely block their reproductive ability. This effect is particularly pronounced in predatory marine gastropods like the common whelk (Buccinum undatum), making them valuable bioindicators for marine pollution. The degree of imposex observed in a population provides insights into the concentration of harmful substances in the surrounding waters. Although TBT has been banned in most countries since the early 2000s, residues still persist in many marine ecosystems and continue to impact whelk populations significantly. |

In addition to chemical pollution, whelks are also threatened by overfishing. In many coastal regions, they are considered a culinary delicacy (see below) and are either caught as bycatch or targeted directly. Intensive harvesting, often carried out without sustainable management plans, has led to notable declines in populations in some areas. Additionally, marine ecosystems are being altered by climate change and ocean pollution. Rising sea temperatures and ocean acidification negatively interfere with the formation of calcareous shells, which are essential for the survival of whelks in the same way as all shell-bearing gastropods.

Within the European Union, steps have been taken to severely restrict the use of TBT as an antifouling agent. Since its ban in 2008, signs of recovery have been observed in affected whelk populations. In the UK and Ireland, initial efforts have also been made to manage whelk fisheries sustainably, through catch quotas and marine protected areas. In the long term, however, only a more conscious use of marine resources and stronger protection of whelk habitats will be able to secure their populations.

![]() BUND:

Die Wellhornschnecke, eine geduldige

Jägerin (In German).

BUND:

Die Wellhornschnecke, eine geduldige

Jägerin (In German).

The whelk has played a notable role in human history. Archaeological finds support the use of robust whelk shells as tools and ornaments. Also, there is evidence that shells were transported over long distances, both by people living at the coast, as well as by traders.

In some cultures, the solid and often beautifully spiralled shells of the whelk served as natural tools - they were used as spoons, water containers, or even as signal horns. Similar to the larger tropical triton shells (e.g. Charonia tritonis), it was possible to produce a booming sound by blowing into the aperture, which could be heard over great distances. In Norse mythology, the sound of a snail horn was associated with the calls of sea giants.

Unlike the dog whelk (Nucella lapillus), however, the common whelk (Buccinum undatum) cannot be used to produce dye.

Common whelk (Buccinum undatum): Nova Scotia, Canada. Picture: Ian Manning (iNaturalist). |

|

Cooked whelks (Bulots cuits) in Normandy. Picture: Wikipedia.nl. |

|

Wist je dat? (Did You Know

This?) In the Netherlands, the common whelk is known as wulk, while in Flanders - especially when cooked - it is commonly referred to as karakollen. This name likely derives from the Spanish word caracoles, which simply means "snails".  Wulloks (karakollen), a traditional seafood snack in Oostende (Flanders, Belgium). Picture: Sandra Fauconnier. The term dates back to the period of the Spanish Netherlands (16th to 18th century), when the region was under Iberian influence. To this day, karakollen are traditionally cooked and sold in clay pots at Flemish markets - a culinary link to the past! |

![]() Wikipedia.nl:

Buccinum undatum (In Dutch).

Wikipedia.nl:

Buccinum undatum (In Dutch).

![]() Nieuwsblad:

‘Karakollen’ zijn écht Antwerps (In Dutch).

Nieuwsblad:

‘Karakollen’ zijn écht Antwerps (In Dutch).

While whelks were once mostly caught as bycatch in coastal fisheries or collected in intertidal zones (see above), there are now efforts to cultivate these snails in water farms (aquaculture). Initial trials have shown promising results, particularly with regard to sustainable production and the protection of wild populations. The main advantage of aquaculture lies in the ability to control water quality and food supply, resulting in faster growth and higher meat quality.

![]() FAO: Whelk (Buccinum undatum): A page by the UN Food and Agriculture

Organization (FAO) with data on distribution and fishery numbers of common whelks.

FAO: Whelk (Buccinum undatum): A page by the UN Food and Agriculture

Organization (FAO) with data on distribution and fishery numbers of common whelks.

![]() NIELSEN,

J.W., Rønfeldt, J.L. (2022): "Appraisal of a

novel fishery of whelks (Buccinum undatum) in Danish Waters". Regional

Studies in Marine Science 56. (Link).

NIELSEN,

J.W., Rønfeldt, J.L. (2022): "Appraisal of a

novel fishery of whelks (Buccinum undatum) in Danish Waters". Regional

Studies in Marine Science 56. (Link).

In the kitchen, whelk meat is considered a delicacy. Its mildly salty, nutty flavour is appreciated in many coastal regions. In France and the UK especially, whelks are a regular feature on seafood menus. In France and Flanders, they are traditionally boiled or served with garlic butter. On the British Isles and in the Netherlands, whelks are often pickled in vinegar and eaten as a snack.

The renowned British celebrity chef Rick Stein, known for his seafood creations, has even featured "whelk spring rolls" on his menu - a modern take on the classic spring roll, combining tender whelk meat with fresh herbs and vegetables. His aim is to show that whelks are not limited to traditional vinegar-and-salt preparations but can also shine in contemporary dishes.

![]() Unsung Seafood:

Rick Stein tries Jack's Whelk Springrolls.

Unsung Seafood:

Rick Stein tries Jack's Whelk Springrolls.

Whelk meat is also a popular food in Asia, especially in Korea and Japan, where it

is used in a variety of dishes.![]() Economic use of marine snails:

Whelks.

Economic use of marine snails:

Whelks.

The common whelk (Buccinum undatum) is one of the largest and best-known

marine snails in European waters, with a range extending as far as Canada and

Greenland. A predatory species with impressive hunting behaviour, it preys

mainly on other snails and bivalves. At the same time, it serves as prey for

many animals, such as oystercatchers and sea stars. Its sturdy shell allows it

to thrive at various depths in the Atlantic, North Sea and Baltic Sea - but

pollution from substances like tributyl tin has severely impacted its

populations. This has made the whelk an important indicator of the health of

marine habitats.

At the same time, it is a culinary delicacy that has

been valued for centuries in coastal regions of Europe. Growing demand for

sustainable seafood could open up new possibilities for whelk aquaculture - an

exciting development that may help reconcile conservation and use. A responsible

approach to managing these animals is essential to secure their long-term

survival and to protect marine ecosystems from further harm. In this way, the

common whelk stands as a symbol of the need to use marine resources with respect

and care.

Latest Change: 25.09.2025 (Robert Nordsieck).