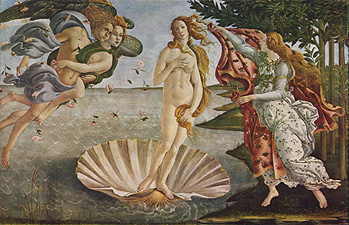

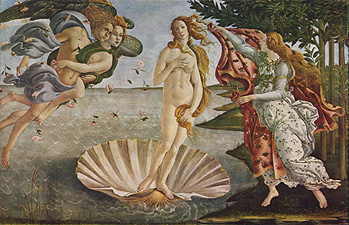

"The birth of Venus" (Botticelli, 1482). Enlarge view! Picture: Wikipedia.

From the earliest time of his evolution, man has had a connection to molluscs, long before he was capable to realise, what a mollusc is.

For the early human tribes living near the coast of the sea, molluscs were a welcome source of protein, easy and undangerous to collect. The appealing beauty of the molluscs' shells soon found the way into human art, be it mussel shells as a plate for the cave painter or important feasts to be introduced by the sound of a triton's horn. The shells of mussels and snails could be used as jewellery, pearls also as an adornment.

"The birth of Venus" (Botticelli, 1482). Enlarge view! Picture: Wikipedia. |

Prehistoric shell heaps, the so called Køkkenmøddinger, bear witness to the amounts of shells processed by a tribe through time.

Not only snails and mussels have been used by prehistoric tribes to craft jewellery. The elongate shells of elephant tusks, scientifically referred to as scaphopods (Scaphopoda) were crafted into bracelets and necklaces, as can be seen in an exhibition of the Asparn (Zaya) prehistoric museum. Even today, elephant tusks are used for jewellery by native American Indians.

![]() Scaphopods (Scaphopoda).

Scaphopods (Scaphopoda).

![]() Prehistoric museum

in Asparn (Zaya), Lower Austria.

Prehistoric museum

in Asparn (Zaya), Lower Austria.

From Greek history we know many scientific names of molluscs in use today. So the term octopus is not Latin, but Greek (πους = foot). Also in the world of Greek mythology, there are stories of molluscs, even if the mollusc only rarely plays the main role. So the goddess of love, Aphrodite, after being born from foam (hence her name), reaches the shore with the help of a large mussel, as we may admire in the painting by Alessandro Botticelli.

Less enjoyable is the story of the monsters Scylla and Charybdis from the odyssey. It may be assumed, that Scylla, a many-armed monster, is in fact an exaggerated description of an octopus. Octopuses, like their mythical relative, remain lurking in a cave and catch careless sea-living bypassers, though not seamen, but crustaceans.

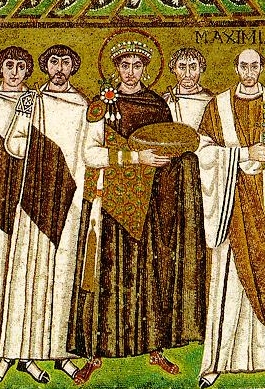

Emperor Justinian I., mosaic in San Vitale, Ravenna. |

Hercules club (Haustellum brandaris), a Mediterranean purple shell. Picture: Roberto Pillon. |

The most important molluscs of antiquity may well have been the purple shell. The famous hoplites of Sparta donned a mantle of the valuable colour, the same, which in stripes decorated the togae of Roman equites ("knights") and senators. At least it was eternalized as "imperial" purple, reserved to the Roman emperor and his Byzantine followers in history. The Byzantine emperor Justinian I. (483 – 565), by his purple coat, is easily recognized among his courtiers. Today, purple is the colour of the Roman Catholic cardinals.

Antiquity's purple colour is usually connected to the Phoenicians in modern Lebanon. But it could even be found earlier, in Minoan Crete of 1600 BC. The purple colour develops as the secretion of a tiny gland near the gills of a sea shell. This secretion of the hypobrancheal gland discolours in contact with oxygen from the air to become purple. As each snail only produces a minimal amount of colour, about 12,000 of them had to be killed at that time to render 1.5 grams of purple dye. In Lebanon today whole hills can be found built by the heaps of shells from the colour industry. Pliny the Elder (23 – 79 AD) in his naturalis historia describes the complicated production process.

Several species of sea shells have been used to produce purple. Among those in the Mediterranean the best known are the Hercules club (Haustellum brandaris), as well as the purple shell (Hexaplex trunculus). In the North, the dog whelk or Northern purple shell (Nucella lapillus) has been used; purple fabrication, for example, is known from the Irish coast in Co. Mayo. Another species of purple shell is the red-mouthed rock snail (Stramonita haemastoma). Purple shells all are relatives systematically; they belong to the family of rock snails or murex snails (Muricidae), a name that also can be retraced to Pliny the Elder's naturalis historia.

![]() Wikipedia:

Tyrian Purple.

Wikipedia:

Tyrian Purple.

Cowry Money. |

In Africa, cowry shells had been used as currency for so long, they were exchanged directly into modern money in some places. Originally the idea to use cowry shells as currency comes from ancient China, from the 12th century BC. From there, the idea spread to India (1st century AD), until by the 10th century, cowry shells were also used in Africa. In the times of Sinbad (during the reign of the Abbasid caliph Harun al Rashid 763 – 809 AD), cowry shells were already widely used as currency in the orient. Until cowry shells were introduced in the Americas by European traders (and readily accepted by the natives) the currency had spread over all of Africa. Their distribution surmounted all known money coins, even the renowned Maria Theresia thaler, an Austrian coin from the 18th and 19th century.

Cowry shell (Cypraea annulus). Source: Wikipedia. |

The advantages of cowry money are obvious: They are durable, difficult to forge, and they have a limited source of supply. But even here inflation struck: Soon cowry shells had to be paid in sacks of hundreds and thousands. Even in the scientific names of shells their role as currency is mirroring: Monetaria moneta (the coin) and Monetaria annulus (the ring). Until the 18th century, the majority of cowry currency came from the Maldives and Lakkadives islands of the Indian Ocean.

![]() Conchological Society of Britain and

Ireland: Shell Money.

Conchological Society of Britain and

Ireland: Shell Money.

Nautilus chalice, Netherlands, ca. 1650. |

At the latest, when Renaissance brought a return to the mythology and art of antiquity, molluscs as well regained some importance as a piece of art, and as an object in painting. Botticelli's (1445 – 1510) already mentioned painting "The birth of Venus" is well known. At that time, the time of discoveries, a growing amount of Tropical sea shells found its way into the halls of Europe. Many of that time's "naturalia" collections have been the historical core collections of modern Natural History museums.

The exhibition "The discovery of nature" in the Natural History Museum in Vienna in 2007 had several exhibits to present, which had been manufactured using mollusc shells. Among those only two shall be mentioned: A lavabo assortment by Abraham I. Pfleger from Augsburg, of around 1585, from a giant clam (Tridacna spec.) and a triton's horn (Charonia tritonis), as well as a chalice from a Nautilus shell originated of the Netherlands of around 1650. The few species of Nautilus left are known to be the last recent cephalopods still bearing an external shell.

Cut-out section of Abraham Mignon (1640 – 1679) "Flower still life with insects and two snails". |

![]() The discovery

of nature: Naturalia in

the art chambers of the 16th and 17th century. Exhibition in the Vienna Natural

History Museum, 2007: .

The discovery

of nature: Naturalia in

the art chambers of the 16th and 17th century. Exhibition in the Vienna Natural

History Museum, 2007: .

In still life paintings, terrestrial snails also can be seen to an increased extent. From the multitude of comparable pictures only two shall be mentioned: Jan Davidsz de Heem (1606 – 1683) "Still life with fruit, flowers, mushrooms, insects, snails and reptiles", as well as Abraham Mignon (1640 – 1679) "".

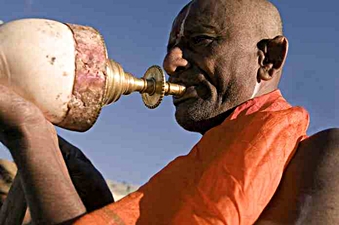

In India the shankha is a symbol for the preserver god Vishnu and his consort, the goddess of riches, Lakshmi. From the Shankha shell (also referred to as Indian chank), a marine gastropod named Turbinella pyrum, trumpets are made that are adorned with carvings and used during religious rituals.

A Hindu priest blowing on a shankha during a feast. Source: Wikipedia. Picture: Claude Renault. |

In art the shankha appears as well, in connection with Vishnu, as a symbol for water it also stands for female fertility and for the holy snakes (nagas). Turbinella pyrum, a member of the Turbinellidae family (Caenogastropoda), is a marine predator snail, which occurs in the Indian Ocean.

![]() Wikipedia:

Shankha.

Wikipedia:

Shankha.

![]() Jacksonville

Shell Club: Turbinella pyrum (a dextral and a

sinistral specimen).

Jacksonville

Shell Club: Turbinella pyrum (a dextral and a

sinistral specimen).

I would like to finish the present page with a personal note: In the course of my biology studies, I once was asked by the professor, what kind of a fossil snail he held in his hand. My identification exercises were unsuccessful, until I was enlightened that the snail in question was in fact an ornament from a tombstone on a Paris cemetery…